How Mary Ann Shadd Cary set the blueprint for abolitionist feminist writing

The first woman to publish a newspaper in Canada was a master of disruption whose influence is still felt

Against the Grain is a monthly column by Huda Hassan examining popular culture and the arts through a Black feminist lens. This is its inaugural edition.

Literature on abolition has been blossoming, from Mariame Kaba and Andrea Ritchie's No More Police: A Case for Abolition to Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson's Rehearsals for Living (now a finalist for the 2022 Governor General's Literary Awards). This week, Kaba and Ritchie announced a new micro press, Sojourners for Justice Press (named for activist Sojourner Truth), that will publish Black feminist and abolitionist works.

Writing on or toward abolition isn't new, though — it is as old as slavery and settler-colonialism. And for many, the role of the writer, and the newspaper, has been integral to the art of dissemination: circulating information and news amongst abolitionists, women's rights advocates, and their communities at large.

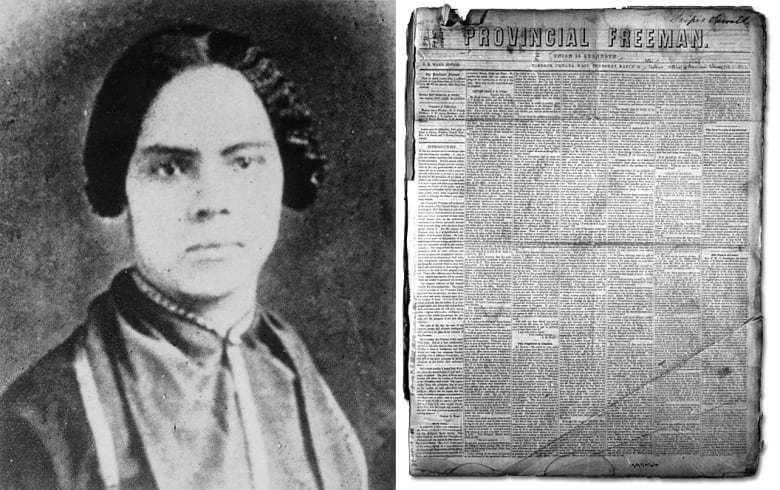

I've been reflecting lately on the history of public writing and abolition that was once so deeply shaped by the work of Mary Ann Shadd Cary. Shadd Cary was the first woman to publish and circulate a newspaper in Canada, The Provincial Freeman — which was also the first Black woman-owned paper to circulate in the United States. An activist, publisher, lawyer, teacher, and journalist, Shadd Cary fought actively for freedom as a material and political reality.

However, despite her strong hand in The Provincial Freeman's editorial, the masthead never revealed her real name. Instead, she concealed her identity by working with Samuel Ringgold Ward, a publisher and abolitionist, who was named as its public editor. She reduced her name to her initials, making her gender unidentifiable. She then brought on another editor, Rev. Alexander McArthur, a white clergyman who could help spread a Black feminist perspective without the ignominy.

Shadd Cary was a master of disruption for all the right reasons; a provocateur committed to gender and racial justice in the 19th century. The conditions of her times called her to this work, and her financial privilege aided her tasks. But it was an extensive family history of resistance, and a desire for better, that lit her path.

Running... from and against

Shadd Cary's story is one of fugitivity. Born in Wilmington, Delaware in October of 1823, she was raised in a household that served as quarters for fugitives on the run. Her homes were always a safe haven for refugees.

Her parents, Harriet and Abraham Doras Shadd, were activists and abolitionists; her father was the first recorded African American abolitionist and the first Black person in Canada to be an elected official. Shadd Cary's sister, Eunice, was the first woman to graduate from Howard (Shadd Cary herself would later become the first woman to enter Howard's law school program). And her brother, Isaac Shadd, also a journalist, was her peer when she created The Provincial Freeman; he was also involved with the planning of John Brown's revolt on Harper's Ferry in 1859.

But the Shadd family's positioning required running, the very theme that became the thread in her writing, teaching, and activism.

At 10 years old, and the eldest of 13 children, Shadd Cary's family relocated to West Chester, Pennsylvania, where she studied at a Quaker boarding school. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, making it "legal" for free Black people and fugitives to be re-enslaved, her family moved north to Windsor, Ontario in 1851, and later settled in North Buxton, Ontario.

Prior to her arrival in Canada, Shadd Cary taught in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New York City between 1839 and 1850. After being invited by publishers Henry and Mary Bibb to teach in Windsor, she created a non-segregated school in Canada for Black refugees and became part of a wave of 19th century Black feminists who fought against homogenized ideas of community.

Through her writing and speeches, she continued running — from the interlocking systems that cultivated the racial and gender norms of her time. She ran from the grips of power; she simultaneously ran toward it, too.

'Why does not somebody speak OUT?'

As Black national desires for African-Americans to relocate to Haiti began to slowly circulate, as a place of refuge from the violent conditions of America, Shadd Cary condemned such pursuits through an open letter in 1861: "An Open Letter to the Anglo-African."

She immediately dismissed the idea as a colonial disposition, describing it as the "bitter pill of colonization sophistry" before asking: "Why does not somebody speak OUT?" And that is exactly what she did, continuously, against the limits of the communities she occupied. Shadd Cary was never afraid to raise her voice and advocate for better, more thoughtful conditions for the Black community — even if it meant going against the grain.

This is the same spirit that Shadd Cary had when she published a pamphlet for distribution in 1852, "A Plea for Emigration to Canada West," detailing a collective migration up north for fugitives hoping to escape capture. One year after distributing her pamphlet, she began to fill in the gaps in political journalism she had identified when reading Frederick Douglass' abolitionist newspaper The North Star.

She created The Provincial Freeman, where she mastered the art of dissemination. It was distributed as a weekly abolitionist newspaper published from March 24, 1853 to September 20, 1857. It was unlike The North Star, which once prompted Shadd Cary to write to Douglass to express her dissatisfaction with the paper's lack of direct action as abolitionists. Instead, Freeman was concerned with political action.

Shadd Cary was never afraid to raise her voice and advocate for better, more thoughtful conditions for the Black community — even if it meant going against the grain.- Huda Hassan

The Provincial Freeman was first circulated in Windsor (1853-1854), Toronto (1854-1855) and then Chatham, Ontario (1855-1857). With the support of her brother, Isaac, and her editorial team, they wrote extensively about slavery abolition with reflections on the Black woman's condition.

But the paper was met with backlash by peers, such as Douglass and Henry and Mary Bibb, for being too wayward.

The rebellious writer

The tone of The Provincial Freeman was militant and rebellious, addressing white America and patriarchy with great audacity in comparison to its contemporaries. The paper actively archived events, meetings, and activities of abolitionist organizing, and gave voice to Black Canadians as well. Utilizing Freeman to produce knowledge integral to her communities, Shadd Cary also organized mutual aid to support fugitives, all at great risk to her personal well being.

"Harriet Tubman, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, and these [19th century Black feminists] had an incredibly radical vision," says journalist and activist El Jones. Jones is the co-founder of the Black Power Hour, a radio show collective with prisoners on CKDU 88.1 FM, and has been a longtime advocate for prison abolition. (In November, she will release her second book, Abolitionist Intimacies, through Fernwood Publishing.)

"This is the work many of us are still doing now," she says. Jones points to Shadd Cary as exemplar to the power of fighting for your voice to be heard, no matter the stakes.

Shadd Cary's approach to journalism, and education, continuously garnered her new enemies — sometimes including old friends.

"It's actually her noted feud with Henry and Mary Bibb that has intrigued and influenced my thought practice as a Black woman writer," says Bee Quammie, a writer, radio host, and TV speaker. "In looking at what both sides represented, how they both aimed to tell Black Canadian stories, and how Shadd Cary was an easy target for the 'unladylike' insult hurled her way by Henry Bibb, these influenced me to sharpen my arguments for and against things that Shadd Cary believed in."

Shadd Cary continuously committed herself to speaking out and against structures of power, even when it landed her in trouble. She ran against the troubling gender norms of her time, subverting her identity to ensure her arguments were heard, and she wrote about the ongoing suffrage movement, sharing news and information to elevate women's rights.

Exceptional outliers, or ordinary people?

Shadd Cary's use of editing, writing, and publishing as resistance strategies to disseminate radical news and reflections is still a tactic used today. However, Shadd Cary was not an anomaly when we position her with her Black feminist peers.

She was a reflection of the epistemic terrains that Black women writers, activists, and community members of the 19th century were concerned with — women like poet, abolitionist, and suffragist Frances E.W. Harper, who was the first Black woman to publish her fiction widely, and teacher, abolitionist, and journalist, Maria W. Stewart, who was the first woman of any race to give a public (and recorded) lecture. A young Harriet Tubman was inspired by Stewart's audacity and later made 19 trips to the South to help 300 fugitives run.

There were existing frictions, some of them necessary, between some of these Black feminist abolitionists, as historians have recounted. Unlike Shadd Cary, Harper was less known to "step on the toes of her male contemporaries." But Shadd Cary, and her peers, were not exceptional outliers; rather, they were a reflection of what their conditions called them to.

We are still fighting to get our voices heard. And to think, this woman was starting a newspaper for her community in the 19th century...- El Jones, journalist and activist

What Shadd Cary and her peers actively fought against is what the Combahee River Collective identified as "interlocking systems of oppression" in the 1970s; or, what bell hooks repeatedly called "white supremacist capitalist imperialist patriarchy"; or, what Kimberlé Crenshaw termed as "intersectionality" in 1989. The necessary work of Shadd Cary and her peers illuminate our paths over a century later.

When we frame historical provocateurs as anomalies of their times, we take away the communal knowledge production and the collective care that shaped them. We also minimize the constraints shaping them. What Shadd Cary understood was the political and social power of newspapers in disseminating reflections and information on their dire conditions, cautioning a future world under these systems.

Crossing the border... again

Shadd Cary and her Black feminist peers subverted public spaces, editorial rooms, education systems, and mastheads in order to be heard. But the viability of sustaining newspapers was fiscally impossible for many. After four years of circulation and discourse, The Provincial Freeman ended in 1857 despite its lasting impact. It lost its funding in the midst of Shadd Cary's feud with the Bibbs family over her anti-segregation stance on education for Black children.

Shadd Cary eventually returned to the United States, and found other ways to direct political action. She helped Martin Delany recruit for his army. She enrolled into a law program at Howard, which was an all-Black male school when she had first applied and was rejected decades prior. At age 60, she graduated and became one of the first women to obtain a law degree in America. After her tremendous feat, she sued the school for discrimination.

She passed away one decade later, leaving behind a family in Buxton, Ontario, who now actively fight for the preservation of her memory.

Over a century after Shadd Cary's time here, her ethos remains vital in a contentious media climate.

"We are still fighting to get our voices heard," says Jones, reflecting on the life and impact of Shadd Cary. "And to think, this woman was starting a newspaper for her community in the 19th century..."

"We need to reflect on what was at stake to do so."