Michael Redhill on life after winning the Giller Prize — why he returned to his poetry roots

Michael Redhill — who won the $100,000 Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2017 for his novel Bellevue Square — returns to his roots as a poet after nearly two decades.

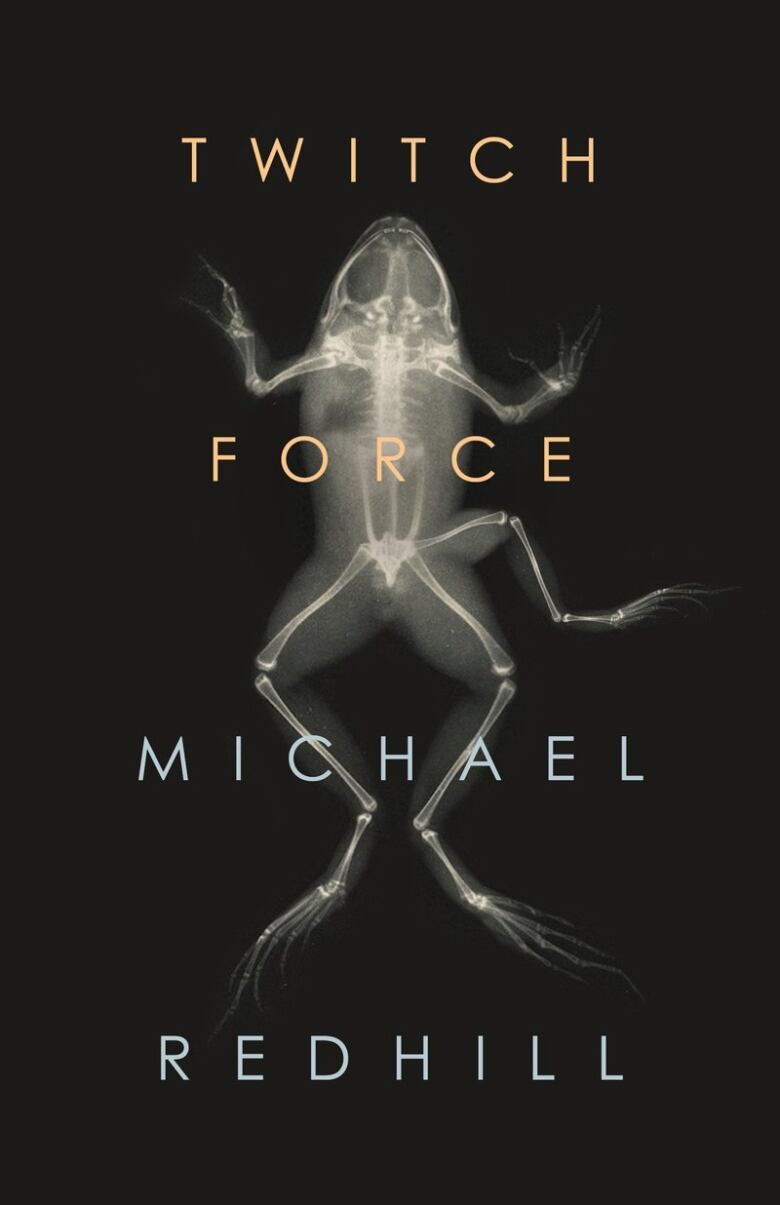

Twitch Force marks Redhill's first collection of poetry in 18 years and brings together poems grounded in the satirical and profound. The collection explores topics such as the family construct, the nature of beauty, love, loss and despair.

The Toronto-based Redhill spoke with CBC Books about his return to poetry.

What was the morning after winning the Giller Prize like? How's life been since for you?

"The morning after, I was a little hungover! It felt like the world was going by very slowly. I don't think I had slept much. It was like any major sudden change in your life. It was a shock, but it was a happy shock. In the months afterwards, there was still a whole lot of touring to do because the book had just come out that fall. I was travelling across Canada and overseas.

"I was kept pretty busy, on and off, for about the first year. I did a lot of book events with the people that run the Giller Prize afterwards. They stayed in touch with me. It still feels like a broadly spread family of some kind."

Does winning a huge award like the Giller Prize provide a sense of validation as a writer?

"I don't think any artist needs a prize to feel validated. It does, however, make you feel surreally set apart from everything you're used to. Especially when you are used to being ignored or being alone in your house at your desk. I think every writer suffers from that imposter syndrome.

"When you win a big prize, your doubts also become much more manifold. I still think in the not too distant future I'll be unmasked as the phony I am. Then I'll wish I hadn't won the Giller. That will teach me!"

After winning the Giller Prize for Bellevue Square, you posted on Twitter an image that revealed you had exactly $411.46 in the bank before cashing your $100,000 cheque. How big was the prize money for you at that time?

Two curious incarnations of Bellevue Square on November 23rd, 2017. <a href="https://t.co/0rkjUmKe5p">pic.twitter.com/0rkjUmKe5p</a>

—@stet_that"Every time a writer gets money, it translates into time — time where you don't have to do any other things but write. The clock started ticking when the money went into the bank. It's been a year and a half and I've been continuing to earn a living as well.

"I'm still able to do what I've been doing all along, which is to stay as close to my desk as I can. I was already working on the next book in the Bellevue Square triptych, which is called Mason of Tunica. I was also finishing up edits for my poetry collection Twitch Force."

Why write a book of poetry at this time?

"Twitch Force took shape over time. The earliest poems were written in the 1980s. But I found, after awhile, that my interests were revolving around looking at certain ways of making a line of poetry and answering the fundamental question of what happens after a line break in a poem.

"What is that about? What happens in the reader's mind? What is that transition for and how can you manipulate it? Poets have been thinking about that since the dawn of time, but it's obviously a worthwhile occupation.

"One of the reasons why the book took so long was because I was very infrequently taken with the desire to write [poems].

"At various times, I might live with the poem for a week, two weeks or months and then it got stuck in a file. Sometimes I would get in a mood and go through all the poems that were in that folder. I would throw some away, rewrite others and try to pick up the signal from them about what they were doing there.

Every time a writer gets money, it translates into time — time where you don't have to do other things but write.

"People speak of occasional poetry, meaning a collection of poetry that was written per occasion, per subject or topic instead of an epic poem for instance, which has a subtext of plot. I wanted to maintain the occasionalness of the poems in this book but also have something swelling underneath all of that, something that was more about how the mind struggles with ideas put into words and not being afraid of leaving out the closure in the poems. That could be problematic for some readers."

Do you consider yourself a poet who is a novelist or a novelist who's a poet?

"I hope I count as just a writer. I've written in enough forms and I'm interested in almost any form. I've never written a libretto, maybe I'll get a chance one day. I love opera but I don't know how I would ever write one.

"I'd like to be thought of as a writer. Why does it need to get pigeonholed except for publicity or commercial reasons? I started as a short story writer before I was the age of 14. Then I wrote poetry and I published poetry first."

Is it fair to say that poetry demands a lot from readers?

"No more than what a painting demands from somebody looking. When you get to the state of mind that allows you to see, hear or pick up the words off the page — be it poetry or prose — it has to do with being with the work. It's not worrying about whether you 'get it,' you know?

I would say to all readers of poetry — just trust what you see on the page. It's not a code, it's not an anagram."

"The first reading of any poem is the same as when you're listening to a piece of music for the first time — it's to be comfortable in new territory and then to see if you pick up the beat.

"I would say that the poems may be difficult on some level, but not a pigheaded way. I'm not trying to shut people out and make them work extra hard. I would say to all readers of poetry — just trust what you see on the page. It's not a code, it's not an anagram."

"I'd come across the term in reading something for research. It's the idea that your muscles do what they've done before. That's what they know to do. But the strength that they do it at has to do with the memory of the last time it was done. All of your muscles are photocopying actions, repeating and repeating, but the signal never gets stronger. It's always dependent upon muscle memory.

"It has to do with potentiation: the moment before something gets catalyzed, whether it's chemical or emotional. And those moments, those twitches into being, is something I wanted to replicate in the poetry."

Would it be too simplistic to draw parallels between a 'twitch force' and your own career?

"It's fair. I've definitely been zig-zagging my whole life. At first it felt like I was trying to see where I fit. But nowadays I feel like going everywhere. If no one stops me, I think that's what I'm going to do."

Michael Redhill's comments have been edited for length and clarity.