Grief and gratitude as families, staff cope with Manitoba's deadliest COVID-19 outbreak

Outbreak in Steinbach, Man., has claimed 4 lives, making it the deadliest at a Manitoba personal care home

It's a cloudy day with a brisk autumn breeze, and George Kehler stomps over a crispy layer of golden leaves on the grass as he walks to a gravesite at the Mitchell Gospel Church Cemetery.

He stops at the foot of a hill of dirt. There is no gravestone at the other end.

"This is where Mum is buried," George says.

The headstone is still being engraved. A pile of dried purple flowers and greenery still lie on top of the mound, left from an Aug. 31 funeral at the cemetery in the rural municipality of Hanover, just west of Steinbach, Man.

It is Sept. 23, exactly a month since his mother, Katharina Kehler, known as Tina, died after contracting COVID-19. She died in her room at Steinbach's Bethesda Place personal care home on Aug. 23 — 12 days before she would have turned 100.

"An hour before she passed away, we got another call saying she was not doing well. Then one of the nurses stayed with her for the last while," George said.

Tina was the first resident at Bethesda to die during a COVID-19 outbreak at the care home that began in mid-August. Three others have died since, making it the deadliest outbreak to date at a personal care home in Manitoba.

The outbreak, which appears to have started with one staff member, has now infected 10 staff members and eight residents, including the four who died.

The last time George saw his mother was three weeks before her death, during an outdoor visit.

"She did not feel very good. I don't know if that was maybe a very small start of what was coming, but she did not feel well, so she did not speak a lot," he said.

The care home allows patients with COVID-19 to receive visits from two family members who are registered as designated caregivers. Before entering, visitors must be fully dressed in protective clothing, from gowns to face shields.

George had a few opportunities to visit his mom after she was diagnosed in mid-August, but he couldn't take the risk — he had recently been diagnosed with cancer and just started treatment.

"It was a … very difficult decision to make for me," he said. "How would I fare if I got COVID, and would that be fair to my family?"

Instead of visiting, he spoke to his mother on the phone. Most of their conversations were focused on explaining why he couldn't visit, he said.

"She didn't understand that whole process of why she couldn't come out, or why we couldn't come in … and that made her even more lonely."

'Always there for us'

But Tina wasn't always lonely. She had many friends at Bethesda Place and was well-liked by the nurses at the care home during the five years she lived there, her son said.

"In her wheelchair, she was always motoring around in the hallways," he said with a laugh. "Even those who were fairly younger than she was, they were not as fast as she was on her chair."

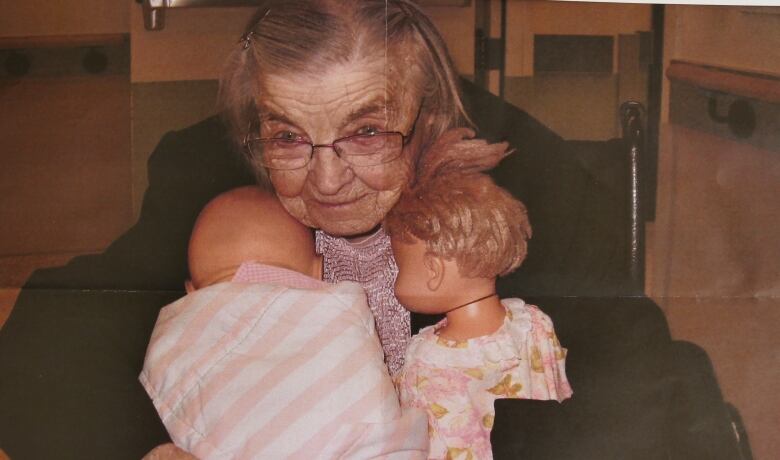

George showed CBC a picture of his mother cradling two infant dolls. In the photograph, she nestles them close to her chest. He said the photo is recent, taken about a month before she passed.

"These were a couple of dolls that she was constantly carrying around as her babies. She'd ask the nurses, 'Hey, I think it needs a diaper change,'" he said. "Because she loved her grandkids, this was one thing she clung to."

Tina Kehler left behind 20 grandchildren and 19 great-grandchildren, in addition to a daughter and two sons, her obituary said.

She spent the first half of her life farming with her husband in the community of Randolph, just west of Steinbach, raising their daughter and two sons. In 1972, their family moved to nearby Mitchell, and then to the city of Steinbach in 2002.

"They were always there for us," George said. "That is the kind of mother she was, always willing to help wherever she could."

4 deaths in less than 2 weeks

The COVID-19 outbreak at Bethesda was declared by health officials on Aug. 17. The province announced the first death at the care home on Aug. 25 — later identified by CBC as Tina Kehler. At the time, there were four staff members and three residents who were infected, including Tina.

Dr. Brent Roussin, Manitoba's chief public health officer, said the only possible link to the outbreak was a staff member who tested positive during the infection period, but not during the period of symptomatic spread.

On Aug. 27, a second death at Bethesda was announced — a woman in her 90s, whom the CBC has not yet been able to identify. The province said at that point that one more staff member was infected.

On Sept. 3, Roussin announced two more residents with COVID-19, in their 80s and 90s, had died. CBC has identified those people through their obituaries, and has reached out to their families for comment.

Those two most recent deaths included Elsie Janzen, of Grunthal, who died on Sept. 1.

Janzen and her husband owned the Janzen Shopping Centre in Grunthal for a number of years, her obituary said. She had two children — a daughter and a son — as well as two grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Janzen led an active community and political life, the obituary said. For 45 years, she sat on the boards for the federal and provincial Conservative parties, and also served on the Manitoba Public Utilities Board and the Manitoba Welfare Appeal Board. She was also a horticulture judge at country fairs.

Eileen Reimer, 90, of Steinbach, died a day after Janzen. Her obituary says she had three children, three grandsons and two granddaughters.

Reimer moved to Steinbach as a teenager and, due to her father's illness, supported her family with many part-time jobs in her teen years, according to the obituary. She played the piano and violin.

Reimer later became a teacher and taught many children in southeastern Manitoba before she married in 1965, says the obituary. She and her husband farmed together north of Steinbach until she was 85, after which she moved into Bridgepark Manor and later into Bethesda Place.

There have been no further deaths linked to the outbreak so far, but the case count connected to it has continued to rise.

On Sept. 17, Roussin said two more residents and one more staff member had tested positive for COVID-19, bringing the number of people infected in the care home to eight staff members and six residents.

More than a week after that, on Sept. 25, one more case of COVID-19 — a staff member — was announced.

The latest tally on Monday added two more residents and a staff member, bringing the outbreak's total to 10 staff and eight residents infected.

Spread in home still a mystery

Roussin said the first person linked to the care home known to have the illness was a staff member who tested positive for COVID-19 on Aug. 3. The investigation into the outbreak was announced on Aug. 17.

But when pressed by reporters on how the virus managed to spread in the care home, Roussin did not provide specific details.

Asked at a Sept. 25 news conference whether the coronavirus spread at the home because personal protective equipment wasn't worn at all times, Roussin said he couldn't confirm the situation at Bethesda.

"We know that PPE is difficult to wear constantly, so there are some lessons learned," Roussin said, speaking broadly about personal care homes.

Cheryl Harrison, the executive director of Southern Health — the health authority responsible for the region that includes Steinbach — said the actual source of transmission at the care home still hasn't been confirmed.

"It's not necessarily been entirely confirmed that it was that worker, so to be honest with you, I could not provide you a clear, determined response to your question," Harrison told CBC News on Sept. 24.

Managing an outbreak is challenging, she said, and the emergency planning is different from responding to threats such as fires or tornadoes, where the situation can be stabilized in a short period of time.

"It's like running a sprint within a marathon.… With COVID, it transmits so easily. In a sense, it's invisible," Harrison said.

"It requires such committed dedication of long hours, detailed planning and significant, immediate response — but over a long period of time," she said. "This threat is quite different than perhaps what we're used to seeing."

The COVID-19 cases at Bethesda Place were the first to be reported at a Manitoba care home. Now, cases are being tallied at eight care homes in the province, and counting. Roussin said the increase in these types of outbreaks is the result of more COVID-19 cases in the province overall.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, seniors in long-term care have accounted for 81 per cent of COVID-19-releated deaths reported in the country.

Staff face anxiety, fear, heightened workload

Harrison said staff at Bethesda Place home have been experiencing anxiety and fear, along with increased pressures in their jobs.

The care home remains at the red, or critical, level on the province's pandemic response system, meaning all residents are isolated in their rooms and visitor restrictions are in place.

Residents are also put into three categories depending on their own level of risk from COVID-19: red, orange and green. Red indicates that a resident has tested positive for COVID-19. Orange means they were in close contact with someone with the illness. Green indicates they exhibit no symptoms and haven't been in close contact with a case.

With residents isolating in their rooms, staff members have to bring in meals three times a day. They also must work with hot, cumbersome personal protective equipment, and maintain physical distancing while providing care.

Staff members know residents as though they are extended family, Harrison said, making the outbreak — and the deaths because of it — "an emotional roller-coaster" for them.

"You have to work as you're also grieving the loss of residents and the families that no longer come and go within the facility," she said.

Heather Wiens has seen how hard the outbreak has been for staff.

She cares for her father, Herb Suderman, 76, who has been living at Bethesda for four years. Last week, Wiens and her sisters were given designated caregiver status, allowing them to visit the care home.

"It is such a tough time" for staff "to see the residents like my dad suffer because of the pandemic and suffer from the lack of their loved ones being able to visit.… They've watched all of this unfold every day," Wiens said.

"The public needs to know how hard these health-care workers are working, and not just physically hard. They're there mentally and emotionally, working very, very hard."

She said her dad has been declining rapidly because of a lack of routine — her mom can't visit, and he's isolated in his room. But she's grateful for the care staff have provided.

"They've been nothing but but amazing with him," she said. "There's nothing they can do about a pandemic."

Concerns over care, transparency

But other families, like Tracey Tallaire's, have growing concerns about the quality of care and transparency at Bethesda.

Her mother, Connie Keast, has been a resident at Bethesda for three years. Keast, who is a former nurse, celebrated her 87th birthday at the care home on July 31.

Tallaire said she's concerned about the lack of communication families have been getting from the care home. She said since the start of the outbreak, the only information she received from staff was that her mother needed to self-isolate because she had been in the same wing as someone who had COVID-19.

Her questions about the risk staff pose to residents, and how transmission started, remain unanswered.

"There are more staff members than actual residents who have gotten the virus. So how are they making sure that doesn't continue?" she said. "And if staff are bringing it in to residents, I'd like to see some policy changes to make sure that that's not possible."

Tallaire said she's frustrated because every time she's asked staff questions, they've told her they don't have the information she's looking for.

"I know, of course, they can't give us details on which person has COVID, and I don't want those details," she said. "But it's just a bit shocking when you read about a death in the news from Bethesda Place and you haven't been notified in any way."

Harrison said along with balancing confidentiality, information might not be available to staff.

"Sometimes those answers are not that easy to respond to, so one could interpret that as being not transparent, but one needs to interpret that also as the answer isn't always that clear," she said.

Tallaire is also worried that with the amount of temporary staff the care home is bringing in due to the pandemic, her mother's care is compromised.

During past visits, she and her sister would comb their mom's hair, encourage her to walk and play her favourite music. But since the outbreak was declared, they haven't been able to see her.

"She has a huge love of music, so we always make sure she has her favourite CDs and radio station on.… Just little things we know bring her joy," she said.

"Staff really doesn't have the time to do things like that, so she's often alone in her room for hours and hours without any interaction."

Finding comfort

George Kehler remembers the day his mother passed. He said he had spoken with the nurses throughout the morning, who told him his mom wasn't eating or feeling well.

He said his mother, who was lonely, often expressed the desire to go home, especially after his dad died six years ago.

In the moments leading up to his mother's death, a nurse who knows his family well stayed by her bedside.

"She was actually sitting there with her and holding her hand," George said.

"It gave us a little bit of comfort that we have such good nurses there."

With files from Holly Caruk and Bartley Kives