Winnipeg sisters say inadequate home-care funding leaves them paying out of pocket, $30K in debt

Amount provided to pay home-care aides through provincial program hasn't changed since 2012

Two Winnipeg sisters who rely on a program for home care say their safety and health are at risk because they're not funded for the hours of care they need.

"When you don't provide enough funding, you're hiring people who are not qualified and trained and in a way, it's kind of risky for us," said Antonia Murgolo, one of 700 clients of the program.

Antonia, 63, and her sister Rosanna, 54, have been enrolled in the provincial self- and family-managed care, or SFMC, program for 13 years.

The program, which is administered by regional health authorities, allows people who need home care to act as managers and hire their own workers in order to live independently at home.

In 2008, when they first enrolled in the program, the sisters were granted just under eight hours of care per day, at $21.40 per hour, by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority.

The sisters both have limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, a disorder that causes progressive muscle weakness. When they signed up for the program, eight hours of care a day was enough, Antonia said.

But since then their condition has deteriorated to the point that the sisters are unable to move without assistance, and Antonia says they now require care 24/7.

Her lungs have been weakened by pneumonia, which means an attendant must connect her to a BiPAP (bilevel positive airway pressure) ventilator for four hours a day and overnight.

"If I go to sleep without it, I would never wake up because I stop breathing when I sleep," she said.

Antonia and Rosanna have been asking the health authority for more care hours since 2015. The hourly rate the province allows for attendants hasn't been increased since 2012.

Antonia said that amount — minus Canada Pension Plan and employment insurance premiums, equipment, and workers' compensation coverage — only leaves them around $14 per hour to pay workers, which is not competitive enough for them to recruit staff.

Racking up debt

They pool the cash they receive for 55 paid hours of care per week and stretch it to cover 24/7 care by reducing the hourly rate they pay their attendants and digging into their own pockets to subsidize the wage.

Antonia has bumped the wage to $18 an hour by using her credit card and line of credit.

"The applicants apply. We noticed a difference, so it's the money. The only problem with that is we are running out of money," she said.

Antonia said they've racked up at least $30,000 in debt to pay the difference since 2014. Her only source of income is a disability pension, which is around $1,000 monthly.

She said she has maxed out on her line of credit and is now making minimum payments on her credit card. But regardless, she and her sister are determined to avoid the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority's regular home-care program.

"I hear horror stories from my dad. My dad is receiving home care," she said. "We're going to do the best we can to save, to live independently in our own place."

A spokesperson for the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority said the province sets the maximum number of paid hours at just under eight per day, but how that money is spent paying workers is up to the client.

"What they are paid is agreed upon between the client ... and their staff, which does allow them to stretch the funding if the agreed upon hourly rate is lower than what the funding provides for," said Kelly O'Brien.

The program risks leaving patients adrift and without adequate support, says the director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics at the University of Manitoba.

"I think it is quite shocking," said Neil McArthur, who is a professor of philosophy the U of M.

"The WRHA and the province are basically condoning a situation where patients are not getting qualified workers" because they aren't being hired at an adequate wage, he said.

"I think all of that raises a lot of difficult worries."

Health minister doesn't rule out increased hours

Health Minister Audrey Gordon, who worked as a director with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority's home-care program before becoming an MLA, wouldn't rule out granting more than 55 hours of care per week.

"It will depend on the services they need and the supports they need … but that is all done in consultation with a physician or their care provider, and their case co-ordinator," she said.

Rosanna Murgolo said there has been no case co-ordinator in their home since 2019 because of COVID-19 interruptions and previous co-ordinators quitting their jobs.

Antonia said she has asked for more care hours during each visit with her case co-ordinator.

"They said we are at the max, so they don't even examine that at all," she said.

Case co-ordinators have a variety of professional designations, including social worker, occupational therapist or nurse, said the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority's O'Brien. There is no physician supervising the self- and family-managed care program.

A client has to be medically stable and willing to co-operate with a safe care plan in order to participate in the program, according to a 2016 provincial report on Manitoba's home-care system.

But it is up to the client to make decisions on their care, including contacting other health professionals such as physicians, O'Brien says.

"In general, we respect clients' independence when it comes to managing their overall care and connecting with their wider care team as they see fit."

McArthur said patient autonomy is important and patients should be given choices, but they need to be safe and informed.

"They need to be given choices with a range of alternatives that can actually meet their needs. So if people need more care … there should be funds for more care that is available," the ethicist said.

"Patients may enjoy certain aspects of the program," he said. "But would they enjoy it if they're in a crisis or something bad happens?"

Hiring uncertified workers

Antonia said with the amount of money provided, they can't afford to hire certified health-care aides. In fact, none of her five part-time staff have any formal health-care training.

"It has to do with the money they give you and that is why we're not getting the right help," she said. "We can't be left alone."

The sisters have hired people who couldn't speak English, which proved risky for them when the worker didn't understand their instructions, she said.

The sisters rely on former staff to train new workers. They typically pay three days of salary to those exiting the job to show new staff how to transfer them out of bed and connect Antonia to her BiPAP ventilator.

The WRHA's O'Brien says in general, home-care staff will not assist clients to put on their breathing mask, "as this is considered outside their scope of practice."

"However, given the complex needs of these clients, these are guidelines only," she said, and direction on using BiPAP machines "is given on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the appropriate specialists."

Antonia's first workers learned how to use the BiPAP machine from a health authority respiratory therapist in 2011. Since then, though, a revolving door of workers have trained their replacements on the way out.

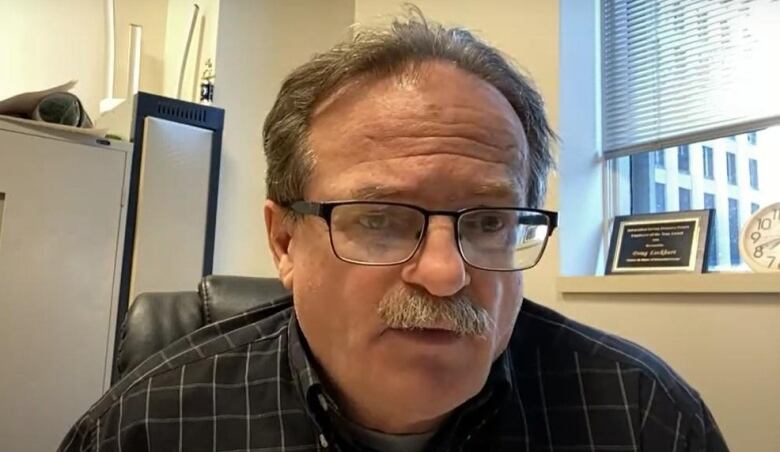

A manager and training co-ordinator with an organization that assists self- and family-managed care program clients with hiring and payroll says he refuses to hire untrained workers.

"They would have to have the appropriate training," said Doug Lockhart, who leads the Independent Living Resource Centre's five-week intensive course for independent living attendants.

When it comes to people who don't rely on his organization to help them with hiring, Lockhart said it's up to the client and the health authority case co-ordinator to determine whether the staff training and hours of care provide enough safety.

"If it wasn't meeting the standard, then [the WRHA case co-ordinator] would not allow them to be a family manager or self manager," said Lockhart.

"So I believe the checks and balances are in place to make sure that those people are having the appropriate care."

Program cost-effective: 2016 report

A 2016 report commissioned by Manitoba's then NDP government determined family-managed care was a cost-efficient program for the province.

The program "replaced the need for resource co-ordinators and scheduling clerks since the client took over these responsibilities," the report said, but noted "an increased need for staff to carry out auditing and monitoring functions."

The Winnipeg Regional Health Authority's spokesperson says if clients are unhappy with the level of care they are receiving or there are changes in the level of care they need, case co-ordinators will work with them to reassess and update their care plans where possible.

If the level of care exceeds maximum funding, case co-ordinators will start a discussion on whether clients should remain in the community and will explore alternative options —which could include institutional care — to ensure they're getting the care they need, O'Brien said.

In an emailed statement, the province says under provincial policy, the cost of home care should not exceed the average cost of a personal care home bed.

"Home care, including SFMC, is not intended to provide 24/7 care," the statement says.

The sisters have been writing letters to the province since 2016, asking for a rate change. CBC obtained several pleas for help directed to former health ministers Kelvin Goertzen, Cameron Friesen and Heather Stefanson.

In March of this year, before she became premier, Stefanson's office responded saying the province is reviewing the program policy and anticipates changes are coming, but the sisters haven't heard anything else since.