'A desperate time:' Why Portage and Main was closed to pedestrians in the first place

Those in charge felt need for drastic change to alter trajectory of a struggling city

The polarizing idea of opening Portage and Main to pedestrians is as hot as a Winnipeg summer, with arguments and accusations being thrown around by those on both sides of the debate — but why was it ever closed in the first place?

Some might say it was the city handing the reins for the iconic intersection to business interests hoping to funnel people through their underground mall, while others have pointed to traffic reports from the time that said gridlock was becoming a problem in the heart of the city and the pedestrians needed to be banned.

But there's much more to it than that.

"It's complicated and there's a lot of political, economic and aspirational factors in all of it," said Richard Milgrom, head of the department of city planning at the University of Manitoba.

The decision has to be framed in the bigger picture of the time, agreed Jino Distasio, director of the University of Winnipeg's Institute of Urban Studies.

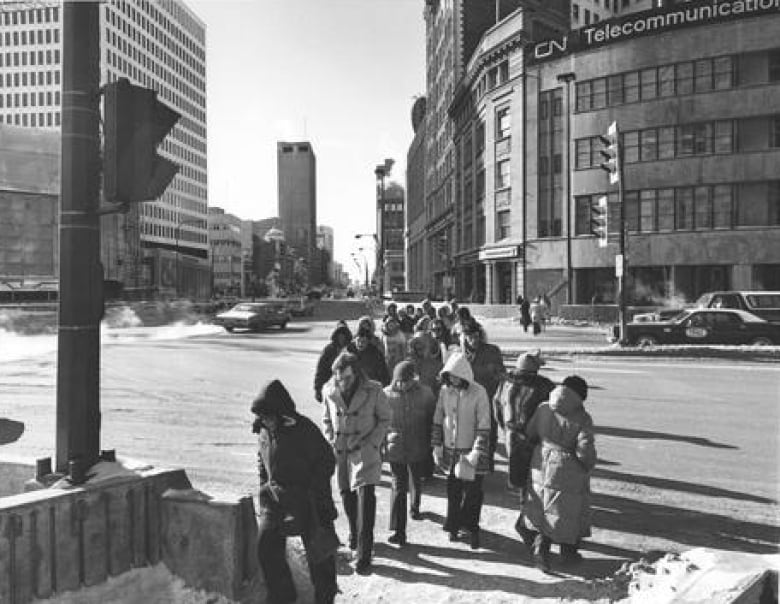

When the intersection was closed to pedestrian traffic in 1979, "Winnipeg was struggling, Main Street was struggling, the downtown was struggling and there was really a sense that we needed to do something of a mega project," he said.

"Really, a lot of it was driven by desperation planning. We were desperate for development and to address a declining inner city."

Winnipeg's core was in the midst of several decades of decline in economic growth, stagnant development and a fading retail environment.

"We were also bleeding more Manitobans than we were receiving," said Distasio. "This was a really interesting time period for Winnipeg."

Suburban growth was drawing homeowners from the core. Malls like St. Vital Centre and Kildonan Place, which opened in 1979 and 1980, respectively, continued to pull away shoppers.

"So if you just look at Portage and Main, if you just look at the bunkers, it's just one piece and you won't understand the bigger complexity that was facing Winnipeg," Distasio said. "The downtown core was under immense threat."

Those in charge were scrambling to figure out how to resuscitate the inner city.

"There, on that corner, it just kind of came to a head. We had to do something," Distasio said.

That's when, in the mid-1970s, the Trizec Corporation made a pitch the city couldn't refuse. It promised to build a five-storey bank on the southwest corner of Portage and Main, which had been a glaringly vacant space for several years, Distasio said.

"There were thinkers who felt that we needed to do something drastic to change the trajectory of a city that was really struggling," he said.

Trizec also promised to construct two office towers with a hotel between them, as well as an underground retail space the city had been contemplating based on another report.

Above-ground pedestrian circle

Throughout the 1960s the city's planning division had conducted a series of studies on traffic movement and concluded that mixing pedestrian and vehicular traffic at Portage and Main would no longer be viable, according to the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation.

Internationally known urban planner Vincent Ponte was invited to create a proposal for the intersection. Known as a proponent of multi-level cities, he proposed a circular causeway built 19 feet above the intersection, which would let people and vehicles move about without interfering with one another.

"That's the way city planners were thinking at that time — there was a big push to separate cars and pedestrians, whether through the skywalk system or some sort of grade separation," said Milgrom.

Some of those decisions were based on the fact the city had just, in 1972, amalgamated with 13 surrounding municipalities to create a much larger metro centre.

"There was a feeling that we were going to go to a freeway model to give priority to the car to attract people downtown. Clearly that didn't work," Milgrom said.

"We've learned since then that downtowns have suffered horribly from this emphasis on [vehicles] and de-emphasizing other ways of getting around."

Going underground

The idea of the overhead concourse was instead redirected underground and the deal was struck with Trizec in 1976, with construction starting the following year.

In exchange for the massive project, the city had to make a number of concessions to Trizec, according to Christian Cassidy's local history blog.

The city had to expropriate and demolish several buildings and build the foundation for the new buildings, as well as the underground concourse and parkade.

Further, they agreed to barricade Portage and Main to pedestrians for 40 years, starting once the project was complete in 1979, redirecting them into the Trizec-owned subterranean mall, the Shops of Winnipeg Square.

The mall connects to a circular hub, known as the circus, which links the four corners of Portage and Main, leading people back to street level through stairs and escalators.

Streetcar tracks and cables

Building the concourse was a major undertaking due to the need to manage traffic that rumbled above on beams of wood, while the ground was excavated.

Piles were driven into the ground to prevent the earth from collapsing and burying the workers six metres below. During the digging, old streetcar tracks and ties, as well as wires and cables, were unearthed, according to the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation.

In the end, when all was said and done, it cost about $80 million, with Trizec covering half. However, it was just one 30-storey tower, the parkade and the underground concourse.

The second tower and hotel were never constructed.

Attempts to save downtown

The city was at the forefront but there was some nudging toward the Trizec deal by the other levels of government, which were also concerned about the city's fortunes.

Two years after the intersection closed, the Winnipeg Core Area Initiative (CAI) was formally launched. It was one of Canada's largest urban regeneration efforts, spanning the decade from 1981-91.

It involved the federal, provincial and municipal governments co-operating to get the city's heart beating again by looking at social, economic and physical renewal.

More than $195 million was spent on programs and development, resulting in massive changes on the north side of Portage Avenue, such as Portage Place Mall, and new housing around Central Park and the Place Promenade apartments.

"It was a desperate time and the Core Area Initiative was seen as one of these massive experimental policy interventions that we had never seen before," said Distasio, noting it drew the attention of governments in North America and Europe.

"You can also look at [the Portage and Main concourse] as a make-work project or an economic stimulus to attract investment in a dying city. Can we say somebody at the time had a vision? Maybe it wasn't the right one or maybe it was for the time," he said.

"The level of urban challenge faced in the city at the time is something people just don't understand now. You need that historic piece to understand where the hell we were as a city then."

City's 'symbolic heart' now 'a traffic conduit'

Some people might say the city gave up a lot in the Trizec deal, with the owners controlling the underground and trying to drive commerce for themselves. But there was hope the office towers, hotel and mall would bring more activity downtown and stimulate other developments.

"I don't see any evidence of that ever happening," said Milgrom.

"At this point, all of the [thriving areas] in downtown are not at Portage and Main. It's in the Exchange District or along the Waterfront and what was the symbolic heart of the city has just become a traffic conduit."

Now, as the 40-year deal nudges up toward its deadline, the idea of reopening Portage and Main has refocused attention on the famous intersection.

"For right or wrong, decisions were made back then about Portage and Main and now we face the same challenge at that corner — where are we going?" said Distasio.

Mayor Brian Bowman pledged during his 2014 election campaign to reopen the intersection if he was elected. Now he is in re-election mode and the topic is cresting, with the city saying in early June that it hopes to open first of four crossings by next fall.

Winnipeg Square, with 45 stores and restaurants, as well as the tower are now owned by Artis REIT, a real estate investment trust, which coincidentally just began construction on that long-overdue second tower.

It has promised the building will be a mix of residential, retail and office space, and at 40 storeys it will be Winnipeg's tallest.

Distasio said he's indifferent on the reopening of the intersection because he agrees with points from both sides.

He would love to see greater openness for everyone to enjoy that corner, however that might come about.

"Right now, I don't find that it's overly accessible. You have to go down stairs that stink like urine and it can be a difficult environment."

'Mazelike' tunnels

A study done for the city by Dillon Consulting, made public last fall, notes the concourse can be intimidating at times.

"The mazelike nature of the tunnels, especially to those who are unfamiliar with them, prevents people from having a full view of their surroundings," it stated.

"Perceived safety will be improved by allowing people to cross at street level where there are longer sightlines and more 'eyes on the street,' both from other pedestrians and travellers in vehicles."

Those who use wheelchairs or other mobility aids that cannot navigate stairs or escalators have significantly longer travel times to cross Portage and Main underground than pedestrians without mobility challenges, the report states.

While there are some elevators, a number are in private buildings that are not open 24 hours a day.

The report goes on to say there are an estimated 15,000 people within 100 metres of Portage and Main on weekdays, making it the densest area of the city. Creating infrastructure that is more conducive to walking could make the area more attractive for urban living.

Distasio notes there are lights where pedestrians can cross about half a block in either direction from Portage and Main.

"If the will of the people is to take down the barricades, so be it," he said.

"But as others have said, there are so many other priorities in the city. The world will not change if those barricades come down."

(PDF KB)

(Text KB)CBC is not responsible for 3rd party content