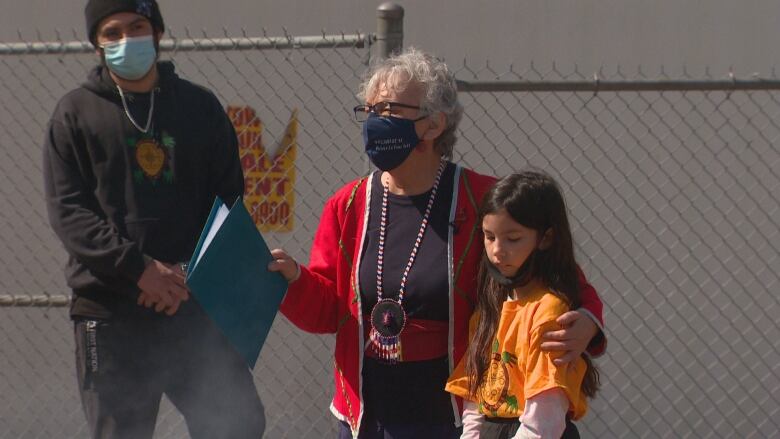

Imelda Perley tries to save Wolastoqey language one spirit name at a time

This elder bestows names to carry cultural teachings and give strength in times of need

The fourth in a series of weekly stories about Wabanaki elders — knowledge keepers, teachers, healers and spiritual guides — who have made remarkable contributions in their own communities and beyond.

Wolastoqi Elder Imelda Perley grew up in Neqotkuk or Tobique First Nation.

Her grandmother named her Opolahsomuwehs (pronounced ah-BLOSSOM-wess), which means Moon of the Whirling Wind. But at Catholic school they called her Imelda Mary.

Perley had tremendous respect for her grandmother and wanted to be like her when she grew up.

"I saw my grandmother as a clan mother looking after everybody in the community," she said.

People went to her grandmother for advice, and Perley saw her grandmother doing a lot for others, through the Catholic Women's League, the Girl Guides, volunteering, gardening and cooking for single moms.

As an adult, Perley became interested in studying linguistics. She thought it could be a way to contribute to the community — to help preserve the Wolastoqey language and ways of life.

She got a university degree and planned to go on to graduate studies.

But elders threw her a curveball.

Some said she should not put their traditional spoken language into written words.

On the advice of Elder Gwen Bear, a confused Perley went to Garden River, Ont., to fast with the Ojibway.

During a shaking tent ceremony there, an Ojibway elder astounded Perley by reminding her of the Wolastoqey name she had lost many years ago.

"Not being able to use it in the school, in the playground, in my own community, I had forgotten it," Perley said.

She felt as if her grandmother was speaking to her again.

"That's when I believed Opolahsomuwehs means something more than Imelda," she said.

Perley came away from that experience with new faith that her ancestors were still around to guide her even if they had passed on to the spirit world.

She said that has been her "guiding light" ever since.

It was her ancestors, she said, who inspired her to start giving spirit names to Wolastoqi children.

Perley said that's after she had a vision of faceless children arriving over a knoll and felt the ancestors were asking her why their children didn't know their names.

"It's important for me to do those naming ceremonies," said Perley, "because of what happened to me — because I went so long without mine that there was a void."

In the past 20 years, Perley has given Wolastoqey names to more than 200 children in communities up and down the river and across the border in Maine.

She chooses the names especially for them based on when they were born and what she knows about them. If she needs help coming up with something, she turns to her ancestors through ceremony, prayer and meditation.

At a naming ceremony this spring in St. Mary's, Perley designated children to be carriers of moon teachings, spring medicine water, healing songs and memories of ancestral waters.

Each of those names contains a cultural message that speaks to the relationship between the Wolastoqiyik and nature.

"Our connection to our environment is being frayed because we're using English more," she said.

She named one child a carrier of beaver medicine. He would have the "strength," she said, "of never giving up on anybody or anything."

"You're good for the community," she told him.

A spirit name kind of gives a person a "twin," said Perley, who can help them find strength when they need it.

Another child she named Winter Wind Talker.

"That's the power of your stories," she told her.

Perley's goal is a "language shift."

"If I just named 15 babies this year, that's 15 words that'll never be lost."

She does an annual blessing in each community so the children don't forget their spirit names and she works with kids on a regular basis to help "make their spirits shine."

"You call on your spirit name to teach you how to overcome anger and use it in a positive way," she said.

"We feast our spirit names every year and ask, have I earned it for another year? Or have I offended the spirits?"

Perley herself has two spirit names — Rainbow Cloud and Grandmother Rain, or, in Wolastoqey language, Monqon Aluhk and Uhkomi Komiwon.

The name Rainbow Cloud came from an elder in New Zealand, but the late Wolastoqi Elder Charles Solomon helped her interpret it.

Perley said it means she is like a cloud carrying Solomon's teachings, which are like water.

The Rainbow part, she said, means she is supposed to be a teacher of all peoples.

Perley said she received her second spirit name, Grandmother Rain, from Cree grandmothers while praying to the water in Cree territory.

She said that's where she earned and received sacred pipes, as well.

The name Imelda still has meaning for her, too. It reminds her of something she has in common with Imelda Marcos, the former first lady of the Philippines.

Marcos is known, among other things, for her vast collection of shoes.

Likewise, Perley has many moccasins — a pair for each type of ceremony she does.

Another of those ceremonies is for burying placentas. The placenta holds DNA that ancestors provided to protect a baby before it's born, she explained.

After birth, she said, it's like the ancestors are saying, "I've done my job. It's now your turn to take care of this child."

So she returns the placenta to the earth, and the ancestors, in a ceremonial way.

It's part of a maternal-child health program Perley started in 2009, called From the Womb to Beyond.

Occasionally, she said, mothers have trouble getting placentas released from hospitals.

Perley hopes someday that won't be an issue, because First Nations will have their own birthing centres.

Some of the other ceremonies she does are baptisms, weddings, sweat lodges, fasts and "letting-go" ceremonies, which she does before a person dies.

"It's such an honour that my people trust me to do that," said Perley.

She hopes the names she has given will be honoured, too.

"When we do powwows, I want them to be in the grand entry," she said.

And she'd like to see the names on a "wall of fame" in every community's health clinic. She has them all written in digital documents and has been thinking of putting them into a book as a retirement project.

It's not what her elders wanted back in the 1990s, but Rainbow Cloud seems to be at peace about it.

She's also done some naming ceremonies for grown women who are interested in becoming clan mothers.

"I'm doing this intergenerationally," she said. "It's going to take other women to do what I'm doing."

"I'm just starting to make tracks."

With files from Myfanwy Davies