Avian flu spreads further into Newfoundland's bird populations — but deaths seem to have slowed

Population has dropped by thousands at Cape St. Mary's

The deadly avian flu that has been blamed for hundreds of dead gannets and murres along Newfoundland's coasts is showing signs of spreading farther across the island.

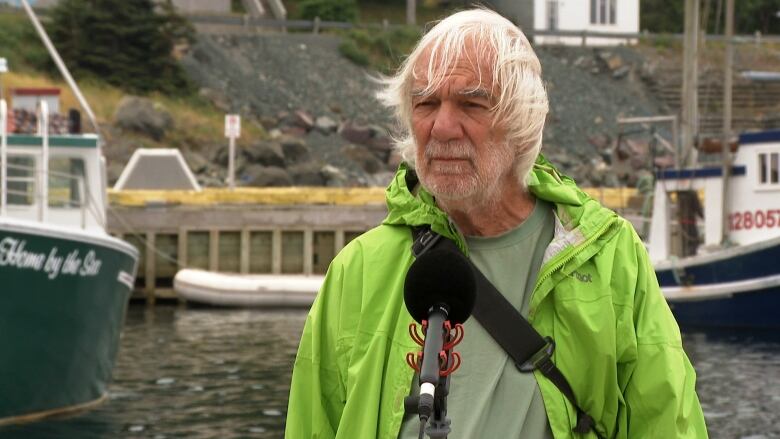

New mortalities have been seen along beaches in Lumsden and Musgrave Harbour, according to biologist Bill Montevecchi, who is tracking the spread of the disease across Newfoundland.

He and his team have taken samples from those birds and are awaiting laboratory confirmation of the cause of death, but Montevecchi says he expects tests will be positive for the H5N1 virus that causes avian flu.

"They're going to be the furthest north positive signals that I know of," Montevecchi said. "We've seen the disease, you know, actually move from the south coast to Cape St Mary's and now to Witless Bay and now most recently to the northeast coast."

The biologist said he's planning a trip to Funk Island, an ecological reserve about 60 kilometres east of Fogo Island, to see if the disease has spread to bird populations there.

It's already led to hundreds of deaths along the Avalon and Burin peninsulas.

'We're missing thousands'

The disease is having a huge impact at the Cape St. Mary's Ecological Reserve, on the southern end of the Avalon Peninsula.

Chris Mooney, who has worked as an interpretation officer at the reserve for two decades, said the population has taken a huge hit.

"For sure, we're missing thousands of birds from this time last year," he said. "It's unbelievable how many dead birds are on the mainland and on the sea stack."

Most of the birds are washing up dead on the shoreline, or dying in the water — but some can be seen perishing on the nesting grounds.

The effects of the disease show up as empty space in otherwise crowded rocks in the reserve. Mooney said the deaths are concentrated among breeding adults — and it's not clear what kind of impact the deaths will have into the future.

"They live an average of 30 years and they mate for life, so we're losing mates," he said. "We don't know the impact. Nobody knows the impact."

Mooney said the deaths do seem to have slowed, and he hasn't noticed any new deaths in the past few days — so he's hopeful the colony is at a turning point.

"This is so new," he said. "I've been here 21 years, I haven't seen nothing like it before. So this is a learning game for everybody."

'You can't do anything'

Montevecchi said he believes the virus is spreading through younger, immature birds who are not tied to one particular colony during a season and instead move among several.

The biologist said there's not much hope that human intervention can slow the spread of the disease or the eventual deaths of the seabirds.

"When there are tragedies that are beyond our control — which this one is unless somebody figures out some miraculous way to intervene — the only thing you can do is you can bear witness."

He said researchers will eventually be able to put together a more comprehensive record of what happened, and how the disease spread.

And for Montevecchi, public participation is a big part of that work; he said he spends hours each day looking at messages and posts on social media about bird deaths.

While the disease will cause a lot of devastation, the biologist says he believes there won't be complete losses of any colonies.

"What I have to focus on is there's going to be survivors, and they're going to be tough."

With files from Carolyn Stokes