How are they going to get that crane down, anyway?

Work to remove crane will begin Saturday

Nearly a week after Hurricane Dorian hit the region, a crane remains draped over a building under construction in downtown Halifax.

The province says work to remove the crane will begin Saturday, but as people stroll by the site on South Park Street near Spring Garden Road, one of the questions they're asking is, "How are they going to get that thing down?"

The twisted hunk of yellow metal is being held in place by gravity. But even now, long after Dorian's 155-kilometre-per-hour winds have dissipated, some pieces can be seen swaying slightly in the breeze.

It's a developer's nightmare.

For a structural engineer, it's no dream either. But figuring out how to take the crane down is definitely an intriguing puzzle to solve.

Fadi Oudah, an assistant professor of engineering at Dalhousie University who specializes in assessing and remediating structures, said he was shocked by the scene when he saw it in person.

"Probably my first reaction was, 'That's a really tough job from a structural engineering perspective and both from [a] contractor and engineering perspective, obviously. And how are you going to remove such a thing?'"

Oudah hasn't done a comprehensive analysis of the site and isn't involved in the removal. But as an observer with a relevant academic background, he's got ideas about how it can be done.

First of all, he says, it's unlikely crews will be able to pick the crane up and remove it in one piece.

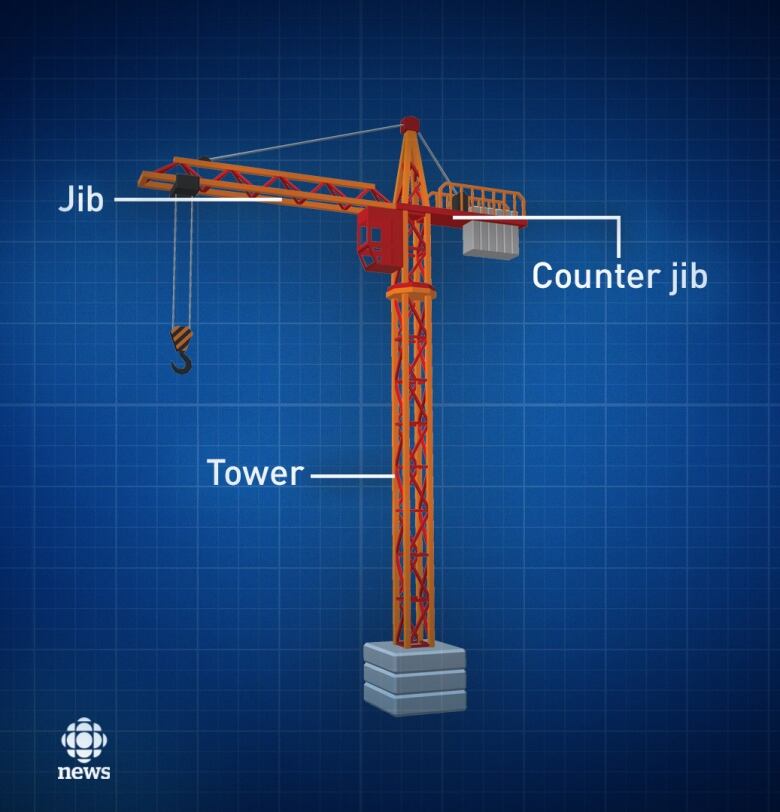

That's because the connecting pieces, like between the tower and the jib, or the jib and the counterjib, have likely been damaged. If the whole crane is picked up, parts could go crashing to the ground.

Therefore, crews will need to cut up the crane. But that, too, could pose a hazard to its delicate balancing act.

"If you are to cut it, you are going to disturb this equilibrium," said Oudah. "And with doing so, some parts of the crane may move. And this may cause some other parts falling down in the streets on the public."

In order to cut pieces off, crews will need to secure them, either with boom cranes or by bracing them to the structure itself, Oudah said.

Oudah said it may be useful to re-examine the safety codes and standards for crane design to consider the possibility of very high winds.

No word on fines for operator

Labour Minister Labi Kousoulis said Thursday it's too early to say whether the operator could face fines.

He said all cranes must be independently approved by an engineer and adhere to safety regulations before they are put into use.

Labour Department staff met with crane operators before the storm to recommend procedures that should be followed during the hurricane, Kousoulis said, and all recommendations were followed at the site of the crane collapse.

"From what I understand, the arm should be swinging freely in the wind so that … depending on how the wind changes it's not putting stress on the structure," Kousoulis told reporters Thursday.

The department is now trying to determine whether post-storm inspections should be done on other cranes to look for signs of damage.

Kousoulis said dismantling a regular, intact crane takes about two weeks, but he's not sure how long it could take to remove this one.

No one from WM Fares Group, the developer responsible for the crane, responded to an interview request from CBC News.

With files from Jean Laroche