How thousands of asylum seekers have turned Roxham Road into a de facto border crossing

Close to 50,000 have entered Canada at the unofficial border crossing point in just two years

Half-way up Roxham Road in upstate New York, a Dead End sign warns that the pavement peters out just ahead at the U.S.-Canada border.

But this once-quiet country road is not a dead end at all. It picks up again on the Quebec side, and this route has evolved into a throughway for migrants from all over the world seeking a new beginning in Canada.

Close to 50,000 have come into Canada in just two years at Roxham Road, stepping across the border at the unauthorized crossing.

It's posing a complicated and intractable problem for the Canadian government.

"They don't bother anybody, they just keep on their way … go out, cross the border," says a bare-chested Tony Hogle, sitting astride a riding-lawnmower. He's lived on the U.S. side of the road for 57 years.

"They're doing a good thing; get the hell out of Dodge," he says, referring to Donald Trump's America, which he adds is, "you know, cracking down on these people all over."

But the majority of those who come here to Plattsburgh, N.Y., by bus, train or plane have spent little time in the U.S., arriving on tourist visas with the intent of treading the footpath to Canada.

When CBC News visited the crossing recently, in one day we met families and single travellers from Pakistan, Turkey, Yemen, Lebanon, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Eritrea, as well as a Palestinian family from the occupied territories. Some arrived with what appeared to be fresh baggage tags from overseas flights into New York. Others had made their way north from Mexico, South and Central America.

In three months this summer, authorities say 5,083 crossed at Roxham Road, averaging 60 a day. That's up from 4,397 over the same period the previous summer.

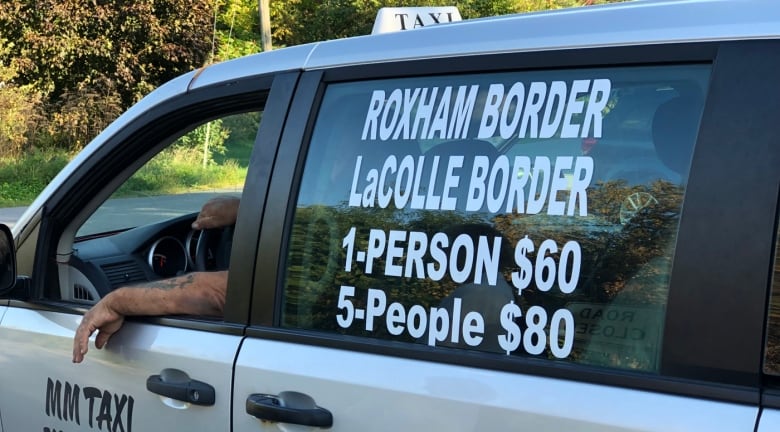

They often prearrange taxis in Plattsburgh for the half-hour ride to the border. Since 2017, the route has become so normalized that taxi companies are branding themselves as border shuttles. A sign on one taxi van brazenly reads "Refugee Border." Another reads "Roxham Border - LaColle Border" and advertises a group rate, with each ride costing between $60 and $80 US, a lucrative and steady business.

A mother wearing a parka, a father and teenage daughter in braids clamber out of a taxi at the end of the road on the U.S. side, pulling their suitcases.

"No hables ingles [don't speak English]," the mother says.

They are stopped just a few feet from a white marker, which defines the international border. The RCMP are waiting.

In Spanish she tells us the family is fleeing Colombia, looking for political asylum because of the threats in their country. Nationals from Colombia are among the top two source countries seeking asylum at Roxham this year; Haitian refugees, so much a part of the surge in 2017, are dramatically down.

The RCMP have well-rehearsed warnings — repeated to every one of the migrants by a team of officers who speak several languages.

"This is not a legal way to come to Canada," says one officer. "There is a legal port of entry five kilometres down the road."

The migrants listen.

"If you cross here you will be arrested by the police, do you understand?"

They do. They've been well briefed by a network of people who've made the crossing ahead of them, and by video on the internet. The routine is practiced, ordered and predictable.

They take a few steps, crossing an invisible frontier before the RCMP officer stops them again.

"One moment, now you are in Canada. You are under arrest for illegal entry to Canada. Do you understand?"

Everyone nods and then proceeds, struggling with luggage and backpacks, holding their childrens' hands. Often the RCMP help with the kids.

Refugee status

From here, the new arrivals will be processed to determine if they can apply for refugee status.

Critics have called them "illegals"; technically it is against the law to cross the border anywhere other than an official port of entry. But once someone is in Canada, it is legal to apply for asylum, a step toward refugee status.

Were they to go to the official border entry nearby, they could be turned back to the United States under a safe-third-country treaty negotiated between the U.S. and Canada that has been in effect since 2004. But it doesn't cover the irregular, unofficial crossing points like Roxham Road, which have become a popular loophole.

"If this were to be closed, I think people would cross at all the places along this long 3,000-mile [4,800-kilometre] border that we share," says Janet McFetridge, an American who lives nearby. "Maybe into very, very unsafe situations where they're in the middle of some field or forest with children, that would be heartbreaking."

As she greets another family, McFetridge acknowledges that for some on the U.S. side, it's easier to be hospitable when people are just passing through.

"We like to talk about how welcoming we are to people who are coming into our area," she says, "but they're also leaving. And that's really a totally different situation."

McFetridge has been coming to the crossing six days a week for two years, on a mission to comfort weary and nervous travellers. She brings baskets of donated snacks and stuffed toys for the many children.

In two years she says she's seen a lot of change on the Canadian side of the border: a new permanent structure for initial processing, a reinforced path bisecting the border with a culvert built underneath, and a more consistent message from the RCMP. Before, "one [officer] would say 'you're going to be deported, and another would say 'welcome to Canada,'" McFetridge says.

"You know not everyone would agree with me, but I just really admire that Canada has a system — whether they're allowed to stay or not, at least they're treated well in the process. We just don't always see that in the U.S.," she adds.

Still, the Canadian government has struggled this past summer to dissuade migrants from taking this route.

After a peak of 9,000 arrivals in the summer of 2017, the federal government sent emissaries into Haitian and Nigerian communities, and launched public information campaigns in other countries like Venezuela and Pakistan, to try and discourage people from using unofficial entry points by warning they are not a free ticket to Canada.

In 2018, the numbers dropped by half. But this past summer they began to rise again.

Shifting attitudes

Of the more than 50,000 who've come into Canada at irregular crossings since 2017, about one-third have been processed under the national refugee system.

About half — 55 per cent — who have had their cases heard have been accepted as refugees. The other 45 per cent have been rejected. But two thirds of the applicants' cases are still pending.

Across the border on the Canadian side of Roxham Road, residents are used to unauthorized crossings — just not on this scale. People have been sneaking across this part of the border for decades, one man told us, often with goods and livestock.

These days the road is a lot busier, with RCMP and transport vans up and down the route. But resident Yvon Carrier says, "it doesn't bug me too much."

The federal government has compensated residents close to the border for the extra traffic and disruption. Carrier got $2,500.

"There hasn't been a lot of problems. This kind of immigration seems to be wanted by the federal government, it's easier to control this way."

But there is a sense that with no solution to stop the flow, and accusations these migrants are jumping the immigration queue (which is not accurate), there may be a hardening of attitudes.

"It's f-ing garbage," says one man outside the post office in Hemmingford, Que., the closest town to the crossing.

"You have plenty of people here [in Canada] with nothing to eat. And then they come over here and get everything they want."

Outside the appropriately named Wits End pub on Frontier Road, a couple of bikers stop to offer their solution. "They should put [up] a fence … that's it. And just go by the door, the front door … not beside it."

But another woman we spoke to says, "C'mon in, you're welcome, we hope they find refuge in Canada."

Beyond the immediate community, Roxham Road has been a sleeper issue in this election campaign, surfacing only occasionally in the overall discussion of immigration.

During a leaders debate (without Justin Trudeau), for example, Green leader Elizabeth May poked at Conservative leader Andrew Scheer for fanning misinformation about the migrants. "You act as if people are illegal when they come here as refugees. Under international refugee conventions, people have every right to come and claim refugee status," she said.

"There is nothing compassionate about forcing refugees to wait longer in refugee camps in places where there is a civil war," said Scheer, "where they have to wait longer because there are some people skipping the line and jumping the queue by coming into Canada."

According to the UNHCR and Canadian immigration authorities, there is no one queue for immigrants. So asylum seekers who cross at Roxham do not take precedence over other refugee applicants, the 75 per cent who come into Canada by other routes.

The NDP, the Green party and the Bloc Québécois would like to suspend or abandon the Safe Third Country agreement with the U.S.

The Conservatives say they would "end the illegal crossings," making the entire border a port of entry. Under the existing treaty, that means asylum seekers would be turned back.

Maxime Bernier's People's Party would fence parts of the border, he says.

The Liberals are under pressure to come up with a solution to stem the flow, but have not addressed it during this campaign. A change this summer to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act means asylum seekers who've already applied in a safe third country like the U.S. would not be eligible in Canada (a majority of the current crossers have not applied in another country).

Other significant changes would require renegotiating the Canada-U.S. treaty, and there are no formal negotiations underway.

Meanwhile, at dawn back in upstate New York, another pair of taxis deliver weary travellers from Pakistan and Lebanon to the Roxham crossing. Kids wipe their eyes as they follow their parents down the now well-worn path, unaware of the potentially life-changing moment.

More from CBC News

WATCH - The National's story about the Roxham Road border crossing: