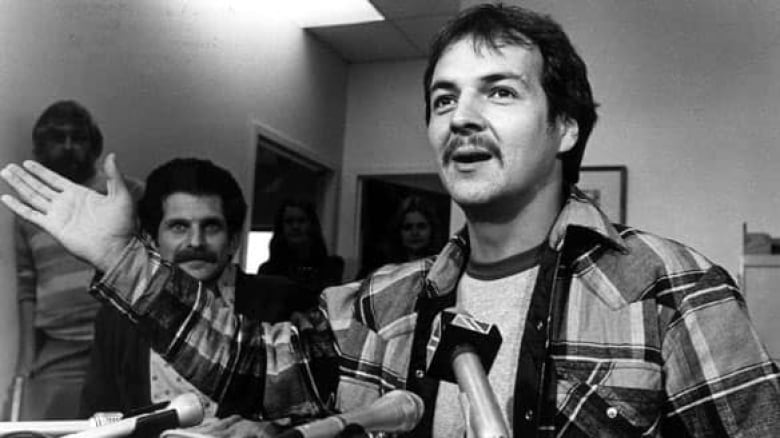

Wrongfully convicted Donald Marshall Jr. dies

Donald Marshall Jr., the man at the centre of one of Canada's highest-profile wrongful conviction cases, died in a Sydney, N.S., hospital on Thursday morning.

Marshall, 55, of Membertou, N.S., had been in the Cape Breton Regional Hospital in intensive care for several days because of complications from his 2003 lung transplant, his brother, Simon, told CBC News.

His family said he had been terminally ill.

In 1971, Marshall was wrongfully convicted of murdering his friend, Sandy Seale, in Sydney's Wentworth Park. Marshall was just 17 years old when he received a life sentence for the murder that was later determined he had not committed.

He was released in 1982 after RCMP reviewed his case and cleared by the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal in 1983 after a witness came forward to say another man had stabbed Seale and several prior witness statements connecting Marshall to the death were recanted.

Though the Appeal Court declared him not guilty, Marshall was told he had contributed to his own conviction and that any miscarriage of justice was more apparent than real.

Roy Ebsary, an eccentric who bragged about being skilled with knives, was eventually convicted of manslaughter in Seale's death and spent a year in jail.

Systemic racism

Marshall, a Mi'kmaq, was exonerated by a royal commission in 1990 that determined systemic racism had contributed to his wrongful imprisonment.

The seven-volume report pointed the finger at police, judges, Marshall's original defence lawyers, Crown lawyers and bureaucrats.

"The criminal justice system failed Donald Marshall Jr. at virtually every turn from his arrest and wrongful conviction for murder in 1971 up to and even beyond his acquittal by the Court of Appeal in 1983," the report said.

Marshall was one of 13 children of Caroline and Donald Marshall Sr., once the grand chief of the Mi'kmaq nation. Following his exoneration, he became known as a "reluctant hero" to the First Nation for his role in fighting for native rights.

'His name should go down in history as a sympathetic individual who had the rights of the Mi’kmaq people close to his heart.' —Chief Lawrence Paul, Millbrook First Nation

Marshall was also the central figure in a landmark 1999 Supreme Court of Canada ruling that guaranteed aboriginal treaty rights to fish and hunt.

He was the primary petitioner in the case after he had been arrested while fishing for eels out of season.

The high court ruling also confirmed that Mi'kmaq and Maliseet in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia have the right to earn a moderate livelihood from hunting, fishing and gathering.

Chief Lawrence Paul of the Millbrook First Nation near Truro said Marshall’s battle for native rights will be his lasting legacy.

"It was instrumental. It was a benefit to the economy of the First Nations across Atlantic Canada, and I think right across Canada," Paul said Thursday.

"So, his name should go down in history as a sympathetic individual who had the rights of the Mi’kmaq people close to his heart."

How the ruling applies to other aboriginals in Canada is still being interpreted.

Marshall will be missed by the people of the Membertou First Nation, where he grew up, resident Tracy Simon said Thursday.

She said she often saw Marshall driving around the community near Sydney, stopping to talk to people. Simon said the people of Membertou recognized all he had done for them.

"He knew what he was doing, and he had the power to do it. You know, especially with what happened to him, I guess everyone would listen to him," Simon said.

"But, he loved it…He loved helping out and getting things done where he seen things weren’t right. He’d get it done, he knew what to do."

Marshall's family is holding a news conference at noon AT.

Marshall suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and had received a double lung transplant in 2003. But he had been suffering from deteriorating health and complications for some time, according to his family.

Halifax provincial court Judge Anne Derrick, who represented Marshall at the inquiry and kept in close contact with him over the years, drove to Sydney Wednesday night to be at his bedside.

"There was a real atmosphere of support and community," she said. "There were a lot of family and friends there. I think it was really important that people had the opportunity to see him.

"I’m very grateful that I was able to go in and see Mr. Marshall. He was unconscious, but it felt good to pay him my respects."

Derrick said that Marshall died shortly after she left.

More legal troubles

Over the last several years, Marshall had faced new legal challenges, including a charge of attempted murder that was later dropped after he and the alleged victim, who Marshall was accused of trying to run over with a vehicle, agreed to participate in a healing circle.

Most recently, Marshall had faced charges of assaulting and threatening his wife.

That matter was scheduled to return to court later this month to deal with his lawyer's allegation that the legal process was abused after Marshall pleaded not guilty to some charges in the case. Defence lawyer Daniel Burman had said he would be seeking a stay of charges on the basis that the prosecution had contravened the notions of justice in the Charter of Rights.

With files from The Canadian Press