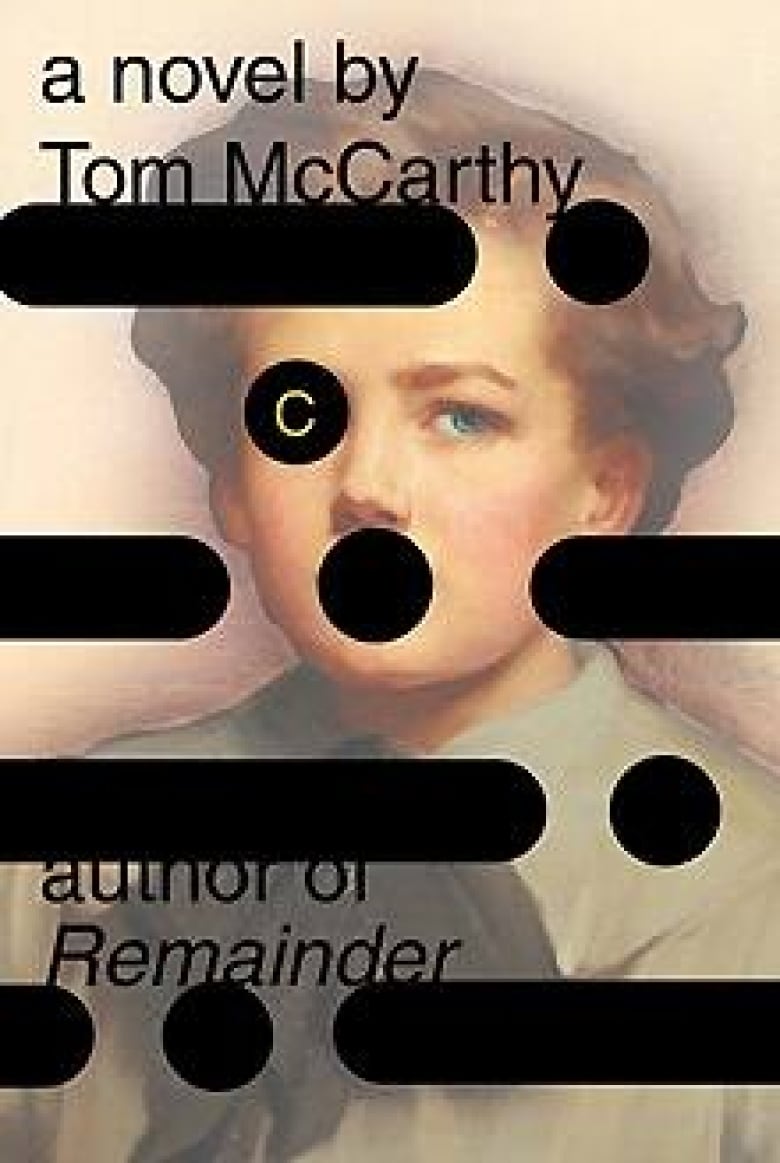

C is for controversy

Booker-nominated provocateur Tom McCarthy stirs up literary debate

The title of Tom McCarthy's new novel, C, stands for seemingly countless things: the surname of protagonist Serge Carrefax; the caul that he is born with in 1898; the copper wire that transmits the wireless signals he sends; the cocaine he ingests in the Royal Air Force in the First World War; the crypt near Cairo where he finds himself towards the end of the novel in 1922; as well as communication, circuits, carbon, curves …

'I would like a realignment of the compass. It's just so f---ing boring, this middlebrow morass that literature, and the whole discussion around it, has gotten itself into.' — author Tom McCarthy

Despite its linear story, the novel is a dense network of ideas and images; readers become detectives, raking the text for clues about its meaning. These connections can seem so pervasive that they carry over into real life. On a cloudy morning in London's Clerkenwell, near where McCarthy lives, we meet and choose a café more or less at random. Only then do we notice its logo: embedded in a shield, a stylized "C."

Over a cappuccino, McCarthy, clad in a camel-coloured shirt and scarf, noted that he just sets up ideas and images – what happens to them is beyond his control. Writing a novel, he avers, is like playing pinball: "You fire a ball up, and there's a certain skill to how you flip flippers and tilt it and nudge it, but ultimately you couldn't anticipate its trajectory around the machine. If you're very lucky, you get into multi-ball mode. It's chaos beyond a certain point. You keep the balls going for as long as possible."

McCarthy's literary pinball wizardry has won him important champions – for one thing, the novel was shortlisted for this year's Booker Prize (won by Howard Jacobson's The Finkler Question). However, the novel's supporters are matched by fierce detractors. C's publication, McCarthy says, has revealed a line drawn "within culture between humanism and a more modernist and avant-garde-informed set of practices," which is "bigger than the Berlin Wall and unbreached." McCarthy sets his camp on the side of the avant-garde, but he camouflages his book as a traditional novel.

The idea for C came to him seven years ago, before he had found publishers willing to take either of the two novels he had already written. The art world, though, had embraced him: as the founder of a "semi-fictional" organization called the International Necronautical Society, he was gaining cult fame in London through performance projects dedicated to "mapping" out and eventually "inhabiting" the realm of death. In 2004, the INS set up a temporary radio station in London's Institute of Contemporary Arts; inspired by Jean Cocteau's film Orphée, it broadcast cryptic, cut-up messages as if from the underworld.

While researching the project, McCarthy was struck by the fact that Guglielmo Marconi and Alexander Graham Bell, the inventors of the radio and telephone, respectively, had originally sought to contact the dead. McCarthy dreamed up a character whose sister dies in early age; working as a radio operator later in life, he finds coded messages everywhere around him, perhaps from his sibling. McCarthy viewed this story as a Trojan Horse into which he could "smuggle" his "philosophical and avant-garde preoccupations," in a "conventional Dickensian trajectory from birth to death in a historical setting. I thought, This is a winner. Surely some f---er's going to publish this one!'"

By the time he completed C last year, his other two novels were in print. Remainder (2005), about a man who obsessively re-enacts traumatic events, was a bestseller and being developed as a feature film; in the New York Review of Books, Zadie Smith argued that Remainder represented a potential path for the future of literature. In the end, C's manuscript generated a bidding war from major publishers excited by the mainstream potential of Serge Carrefax's story.

But C is hardly a conventional Bildungsroman charting the hero's growth to maturity and social integration. The book suggests that Serge, like the communications networks he uses, is made up of nothing more essential than a shifting web of desires and ideas, carbon and cells. So tightly bound is he to the technological, historical and cultural developments of his time that he comes across as unreflective, a symptom of his time rather than a catalyst of change. C has been hailed as "the remix the novel has been crying out for" (the Sunday Times), and while McCarthy professes pleasure at this, he insists he's not an evangelist for avant-garde literature.

"I don't feel some need to convert Middle England. It's not like I'm going on Oprah and [British talk show] Richard and Judy and saying, 'Man, reading Alain Robbe-Grillet – it will change your life!' At the same time, I would like a realignment of the compass. It's just so f---ing boring, this middlebrow morass that literature, and the whole discussion around it, has gotten itself into."

Grand pronouncements such as these have stoked fires of invective in the press; The New Statesman's reviewer has claimed that McCarthy is "the most galling interviewee in Britain." This statement is true only if your ideal interviewee is a platitudinous bore – McCarthy is much too mischievous, sharp and entertaining to fit the bill. In the U.K., he quips, "I think the most intelligent review [of C] has come from YouTube – that one where the person setting it up put straw inside the book. The commentator rates the book depending on how eagerly the rabbit nibbles."

Audrey the Rabbit's response to C was to chew contemplatively. Perhaps she has the right tactic. Serge's story demands to be savoured, as the reader loops back to earlier passages that are cast in new light by later revelations. To do so offers many pleasures, among them the sly, satirical correlations of the early 20th century with our contemporary world, from paranoia about Middle Eastern terrorists to the drug-addled excesses of minor celebrities. History itself, McCarthy suggests, works in circuits and circles.

What you won't find in the novel, however, is a set of Dan Brown-style answers to the codes and mysteries it sets up. For McCarthy, literature is "a meaning-machine, and it doesn't generate its own meaning." In other words, readers must do so themselves, working with the text. "And then the question is, what's just arbitrary and fanciful, and what's somehow legitimate? This is a question that doesn't have a straight answer – or at least not one that I know."

Tom McCarthy appears at an International Festival of Authors event in Sudbury, Ont. on Nov. 4.

Mike Doherty is a writer based in Toronto.