British scientists investigating new strain of coronavirus, but downplay concerns

Scientists say it's not clear if the variant is any more infectious or would be resistant to the vaccine

British scientists are trying to establish whether the rapid spread in southern England of a new variant of the virus that causes COVID-19 is linked to key mutations they have detected in the strain, they said on Tuesday.

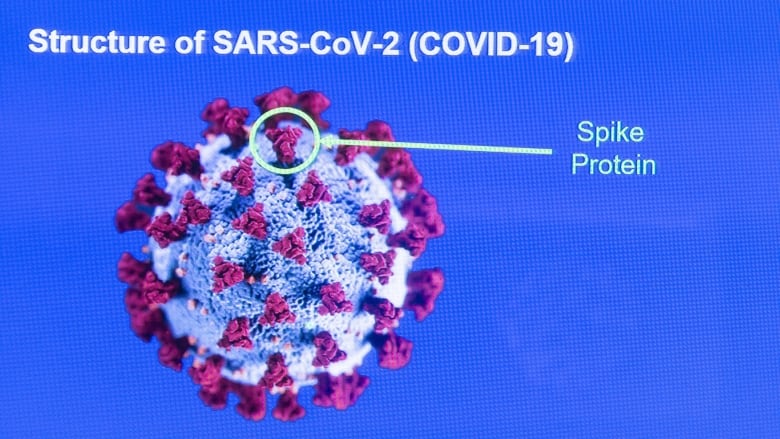

The mutations include changes to the important "spike" protein that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus uses to infect human cells, a group of scientists tracking the genetics of the virus said, but it is not yet clear whether these are making the virus more infectious.

"Efforts are under way to confirm whether or not any of these mutations are contributing to increased transmission," the scientists, from the COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium, said in a statement.

The new variant, which U.K. scientists have named "VUI - 202012/01" includes a genetic mutation in the "spike" protein, which — in theory — could result in COVID-19 spreading more easily between people.

The British government on Monday cited a rise in new infections, which it said may be partly linked to the new variant, as it moved London and many other areas into the highest tier of COVID-19 restrictions.

As of Dec. 13, 1,108 COVID-19 cases with the new variant had been identified, predominantly in the south and east of England, according to a statement from Public Health England.

"So far, there is no evidence the symptoms are any worse or different from other variants of this coronavirus. And there are many variants," said Britain's Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty.

"It just happens that this one has quite a few more mutations than some of the other variants and so that is why we have taken it particularly seriously."

Whitty said that there is nothing to suggest the symptoms, the testing or the clinical outcome for this variant are any different either.

Not 'a major issue'

The COG-UK scientists said there is also currently no evidence that the variant is more likely to cause severe COVID-19 infections — or that it would render vaccines less effective.

"Both questions require further studies performed at pace," the scientists said.

Leicester University virologist Julian Tang told Reuters he believes the new strain would still be vulnerable to the vaccines developed to combat the pandemic.

"The average member of the public on the street shouldn't worry too much about this. I don't think it's a major issue," he said.

"I think it's interesting from a virologist point of view looking at how the mutation changes over time, but it doesn't really affect clinical severity, it almost certainly doesn't affect the vaccine response and protection."

WATCH | British Virologist explains why there is no need to worry about new coronavirus variant:

Mutations naturally arise in all viruses

Mutations, or genetic changes, arise naturally in all viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, as they replicate and circulate in human populations.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, these mutations are accumulating at a rate of around one to two mutations per month globally, according to the COG-UK genetics specialists.

"As a result of this ongoing process, many thousands of mutations have already arisen in the SARS-CoV-2 genome since the virus emerged in 2019," they said.

The majority of the mutations seen so far have had no apparent effect on the virus, and only a minority are likely to change the virus in any significant way — for example, making it more able to infect people, more likely to cause severe illness, or less sensitive to natural or vaccine-induced immune defences.

Potentially similar to flu vaccine

Tang said it may be that, as with the flu vaccine, the COVID-19 vaccine may need to be tweaked regularly, too, to fight new strains.

"So maybe a year from now, you might see a few more new mutations that may start to affect the vaccine. So the vaccine for the year after next may have to be tweaked with a different protein antigen coding gene to fit the new virus. And we do this for influenza every year. So it's not a big thing. It's not an alarming thing."

WATCH | Tang explains how the COVID-19 vaccine may be much like the annual flu vaccine:

Susan Hopkins, a medical adviser to Public Health England, said it is "not unexpected that the virus should evolve, and it's important that we spot any changes quickly to understand the potential risk."

She said the new variant "is being detected in a wide geography, especially where there are increased cases being detected."

With files from CBC News