Indian status card delays impact health-care access

New cards designed to protect against fraud and identity theft

It has been more than three years since the federal government announced a new secure Certificate of Indian Status card, but thousands of First Nation people across the country still don't have them.

And some say it's impacting their ability to access health benefits.

It's very frustrating because without the treaty card, I have a hard time to get my medical, without it I can't get my dental work done, I can't get my eyeglasses.- Bernice Bighead, Sturgeon Lake First Nation

Bernice Bighead from the Sturgeon Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan has been trying to get a new card for three years.

"It's very frustrating because without the treaty card, I have a hard time to get my medical, without it I can't get my dental work done, I can't get my eyeglasses," she said.

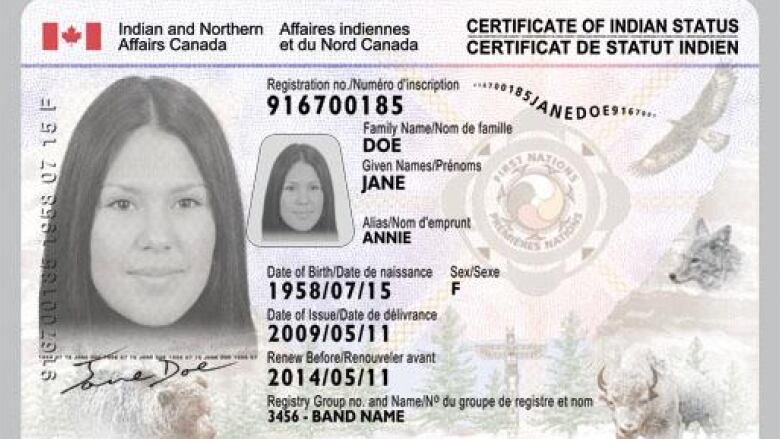

A status card is an identity document issued by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) to Indians registered under the Indian Act.

Currently, there are about 800,000 status Indians in Canada.

Dwight McCallum is the membership clerk with the Peter Ballantyne First Nation in Saskatchewan. He said there are 2,000 people in his community that still need a status card.

"It's because Ottawa is controlling the number of cards that are out there ... they keep saying that these secure cards are supposed to be coming out, so they want to limit the number of paper laminate cards out there."

The current status card is a paper document laminated in plastic, which has raised concerns about forgery or counterfeiting. The new cards will include enhanced security features and meet an international standard for identity cards.

"It's the first truly secure indigenous document throughout the world," Alex Akiwenzie, manager of First Nation relations and partnerships with the Indian and Northern Affairs Department, told CBC News in 2009.

With extra security features such as a hologram and a scannable ID card number, as well as the usual picture and name, the card complies with U.S. Homeland Security requirements.

That means status Indians with the new card can cross the border, by land or by sea, without a passport.

The new card also identifies the holder's First Nation affiliation.

Doug Gamble from the Beardy's and Okemasis First Nation in Saskatchewan said the application process was complicated, but he eventually received his new card after six months.

"You can make no mistakes in the application. And once that process is approved at the office here, then it's sent off to Ottawa, then the reply takes a long time ... and if there is a mistake made, they will send the application back and you have to correct it over here and then send it back again."

Aboriginal Affairs declined an interview but said in a statement that providing the new cards is "a priority of our government." Annually, AANDC says about 85,000 status cards are issued.

With files from Ryan Pilon