Cannabis growers get creative to ease power demands of pot

Innovative scientific, engineering ideas are reducing the electricity demands of producing pot

Legalization may be taking the business of cannabis out of the shadows, but there's an inescapable truth in the tangled mess of extension cords and intense lighting rigs used in clandestine basement grow-ops.

Pot requires power. A lot of it.

From lights and heating to pumps and ventilation fans, it's estimated that it takes about 2,000 kWh to make a pound of product using traditional growing methods. That's close to how much electricity an average Canadian household uses in two months.

"We're not quite sure what the impacts of marijuana growth will be," says Chuck Farmer, director of stakeholder and public affairs at Ontario's Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO).

"We do predict that demand will go up slightly in the next 18 months."

At 47, Ontario has the most licensed cannabis producers and is currently in a good power supply situation, according to Farmer. The IESO forecasts the marijuana business will represent less than one per cent of Ontario's total electricity consumption.

While the Canadian grid should be able to absorb the extra load from the rising demand for cannabis products, electricity isn't cheap.

Commercial producers are looking for ways to drive their costs down, and that's fuelling a market for innovative scientific and engineering ideas to help soften the power demands of producing pot. And that research is delivering some interesting spin-off benefits, too.

Bright ideas

"[Cannabis] is traditionally done in this kind of guerilla horticultural style," says Brandon Newkirk, marketing communications manager at LumiGrow Inc. in Emeryville, Calif.

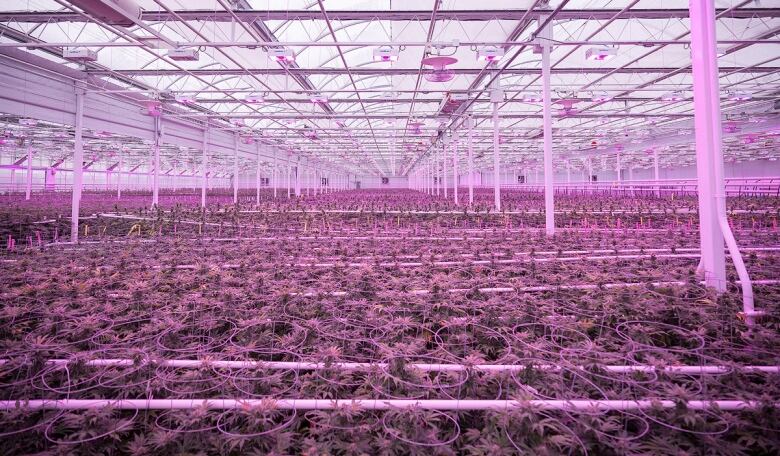

"Now everything is moving to very much enterprise-type, greenhouse-style horticulture. So the way that they were growing vegetables and flowers for a very long time is now being adopted to cannabis."

"What we have here is a situation where you control different ratios of light," explains Melanie Yelton, LumiGrow's vice-president of research.

"And as you control those ratios, the plant will respond in a different way."

"I really stress that every single different variety can respond in a different way," she says.

"Generally speaking, if we reduce the blue and increase the red [light], we'll get a reduction of the THC. If I increase the blue, I'll get an increase."

Ideas to save the world

Besides light, cannabis plants hunger for water and nutrients.

Located not far away from LumiGrow, a tech startup called GrowX is researching aeroponics techniques that could make growing cannabis more efficient.

"Aeroponics allows you to grow without any medium, no soil," explains CEO and founder John Paul Martin.

Another benefit of aeroponics is that it can be done anywhere, including multi-storey buildings in cities.

This kind of "vertical farming" reduces the amount of land needed to grow cannabis, and potentially cuts the distance that the product needs to travel to market.

"This is really trying to move us towards a more regenerative food system," Marin says. "By moving high-impact crops inside, we can recycle more, we can do less damage to ecosystems."

Solving a world food crisis may seem a lofty goal to put on the shoulders of cannabis growers, but aeroponics research being undertaken for the pot industry holds the same promise of boosting efficiency for other types of agriculture.

"Farmland … is getting smaller and smaller, cities [are] getting bigger and bigger. So if you could build a vertical farm in the middle of the city, a small area, you can produce many times more plant material than you could do outside of the city."

Old school, new tricks

It's not just new technology that's helping drive efficiency. Pot growers are also drawing on engineering brainpower and techniques from other fields.

"Thanks to legality [of cannabis], you can get certified professionals to sit and think with you — to design, create, think and operate," says Bruce Linton, CEO of Canopy Growth. "The effect of that is that you get more efficient."

Linton describes one method that takes advantage of Canada's cold climate to cut electricity costs.

Heat created by high-pressure sodium grow-lamps is transferred to water, which is then piped outside. The outdoor temperature difference, combined with a glycol-based system, cools the water. Then it's run back into the building where the colder pipes sap excess humidity from the air before again pulling heat from the lights.

"I'm doing it because I don't want to waste anything. It's a cost problem I'm solving."