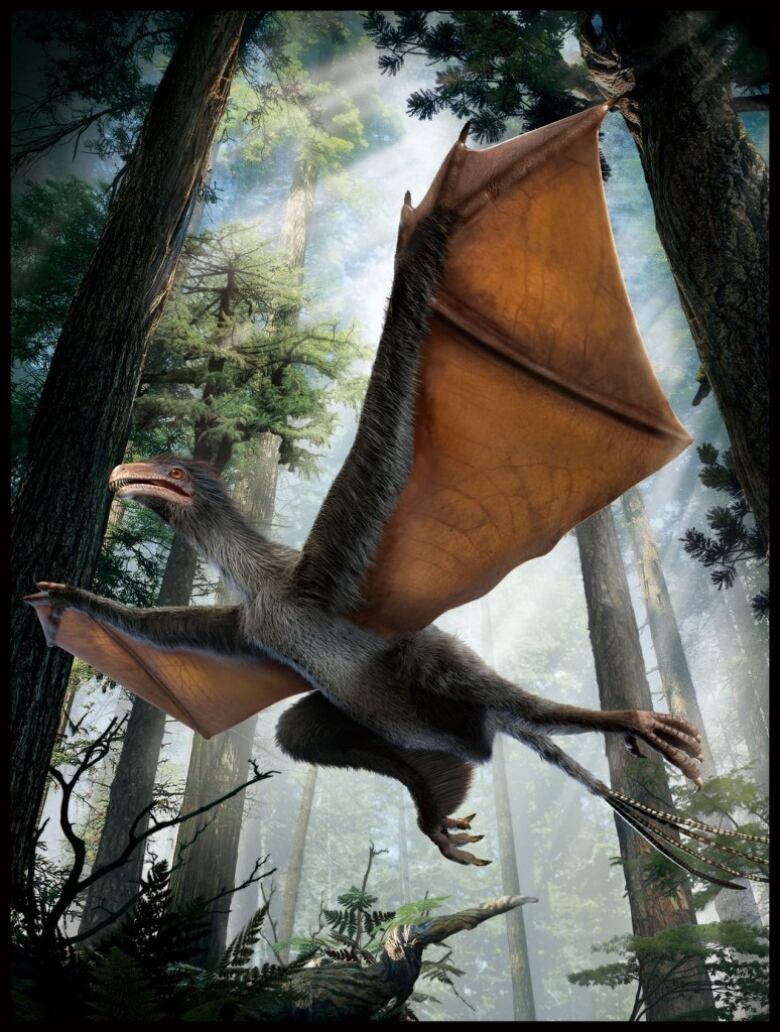

Tiny dinosaur may have flown with bat-like wings

Bat-sized dinosaur had special bone that seems to support flight membrane

Dinosaurs may have evolved into flying birds with feathered wings, but new research suggests they may also have experimented with completely different flight gear.

I don't blame them for being skeptical because it's weird.- Corwin Sullivan, paleontologist

A dinosaur with hair-like feathers that lived in China about 160 million years ago during the Jurassic period appears to have had membranous wings, like those used by bats or flying squirrels, scientists reported today in Nature.

It's the first-ever dinosaur found with wings similar to those of the mythical dragon.

"What we've found is just really strange," said Corwin Sullivan, a Canadian paleontologist working in China who co-authored the paper.

But he said the research team was unable to come up with any other possible explanation for the fossil's strange anatomy."And I don't blame them for being skeptical because it's weird."

- Coming up: Corwin Sullivan talks to Quirks & Quarks May 2 at noon on CBC Radio One

- New dinosaur finds soar in 'golden age' of discovery

- Bizarre vegetarian T.rex cousin found by boy, 7

A farmer discovered the fossil dinosaur, named Yi qi (which means "strange wing" in Mandarin) in Hebei province in northeastern China. It weighed about 380 grams and had a wingspan of around 65 centimetres making it about the size of a pigeon — or a large bat.

The Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature acquired the fossil in 2007, and it was later studied by museum director Zheng Xiating and Xu Xing, a paleontologist who works at both nearby Linyi University and with Sullivan at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

'Blind luck'

While Sullivan was visiting, they showed him a strange bone protruding from each of the dinosaur's wrists.

"We were all very puzzled by these unusual structures," he recalled in a phone interview with CBC News. "We were tossing around ideas for what they might be and none of us could come up with anything very plausible."

Later, "sort of through blind luck really," Sullivan was doing some library research for a book he is writing about the Chinese fossil record, when he stumbled on a passage about flying squirrels in a text book. It noted that the animals have a rod of cartilage extending from their wrists or elbows to support a flight membrane.

"I thought, 'Wait a minute - that strange dinosaur I saw in Shandong had rod-like things coming out of its wrist.'"

Sullivan shared the information with Xu, who re-examined the dinosaur fossil and found "bits of sheet-like soft tissue that seemed to be parts of the actual flight membrane."

Always used for flight

But the researchers were really convinced after seeing how many different animals with flight membranes had similar rod-like structures, including bats, some gliding marsupials and ancient flying reptiles called pterosaurs.

"Nothing that has that kind of structure seems to use it for anything else," added Sullivan.

Zheng noted that Yi qi is a close relative of birds, but evolved at a time when dinosaurs were just developing flight.

"It reminds us that the early history of flight was full of innovations, not all of which survived," he added in a statement.

Unfortunately, the preservation of the fossil was patchy, the researchers weren't able to see the size and shape of the membrane was or what its feet looked like. That makes it hard to confirm how the Yi qi may have lived and flown.

The researchers suspect it climbed and glided among the trees of a forest surrounding a lake, full of other small, feathered dinosaurs, a variety of mammals, pterosaurs, lizards, salamanders and insects. The climate in northern China at the time would have been very warm. Yi qi probably ate insects, small animals and fruit with its peg-like teeth, Sullivan said.

He and his colleagues are very interested to hear whether other paleontologists agree with their interpretation of the fossil, he added, or whether they have any other ideas about what the strange bone on the Yi qi's wrist may have been for.