Ukraine crisis: 7 questions answered

What drove Vladimir Putin to deploy troops in Crimea? What might he and West do next?

No one saw it coming. That's the one thing most observers of Russia's recent military incursion into Crimea agree on. While many expected President Vladimir Putin to reassert Russia's control over its strategically important naval base in the semi-autonomous region following the ouster of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, few expected him to do it so brazenly.

Although academics who study the region are feeling gun shy these days about making predictions, we managed to get three experts to answer some key questions about the crisis and how it might evolve.

1. What was Putin thinking?

• Humiliation. The overthrow of Yanukovych was "deeply humiliating" for Putin, and it's possible he wanted to respond aggressively to show his own people that Russia is not weak and won't be humiliated, said Lucan Way, a political science professor in the Centre for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at the University of Toronto's Munk Centre for Global Affairs.

"Russia really hates it when it feels disrespected, and sometimes, it likes to do things just to show that it matters, even if there is no obvious end game," Way said.

Resentment over past humiliations that Russia has suffered at the hands of Western powers since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 has characterized Putin's reign, which has been largely about overcoming those humiliations and reasserting Russian power, says Terry Martin, the George F. Baker professor of Russian studies in Harvard University's history department.

One of those humiliations was watching NATO expand into Russia's backyard, despite Western assurances that it would not. Putin has made it known he won't tolerate further incursions, and his actions in Crimea could be read as a means of keeping NATO from its door by preventing another ex-Soviet republic from being absorbed into the military alliance.

"This is a country that has felt humiliated, and some of that humiliation is 'get over it,' and some of that humiliation is justified," said Martin, who also heads Harvard's Davis Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

• Discrediting the Ukrainian revolution to forestall a similar one at home. Russia's intervention in Ukraine sends a message to Russians that "this is what happens when you have these kind of revolutions: you have total chaos and civil war," Way said.

• Calculated intimidation of the new government. In some respects, the best-case scenario, says Martin, would be if Putin were simply using the Crimea incursion as a way of intimidating the new Ukrainian government into negotiating an agreement that would guarantee greater sovereignty for Crimea and a significant role in the new government for eastern regions more oriented toward Russia than the West.

• Response to Western aggression. When looked at through the lens of Putin's political rhetoric, which has painted the events in Ukraine as a revolution fomented by the West that has installed an illegitimate regime of nationalist thugs intent on bringing Ukraine into NATO, the events amount to an act of aggression that warrants a response.

"If you really believe the West has overthrown a legitimately elected pro-Russian president and fascists have taken over Kyiv, then I think their [Russia's] actions make a little bit more sense," Way said.

2. What will Putin do next?

Although the situation is evolving rapidly, at this stage, few in the international community believe that Putin will go so far as to take over other parts of Ukraine, namely, the eastern regions that favour an alliance with Russia.

"It will be difficult for Russia to do what they did in Crimea — that is, to organize the takeover of, say, [the eastern city of] Donetsk … without an actual invasion, and an invasion raises the temperature on the foreign affairs scene so much that I just don't think that Putin would risk it," said Martin. "The temperature has already been raised enormously."

There's very little the West can do.… You really cannot tell Putin what to do. —Lucan Way, political scientist, University of Toronto

While many would consider Russia's deployment of troops in Crimea a de facto invasion, Martin says evidence so far suggests most of the troops were already in Crimea as part of the Black Sea fleet — rather than being mobilized across the Russia-Ukraine border in the east, for example.

"It's a bit semantic," says Martin. "Let's say it was a moral equivalent of an invasion. They did it, but they didn't do it without local help.… I don't know how much local Crimean citizen paramilitaries were involved. That's all part of the stuff we may never know."

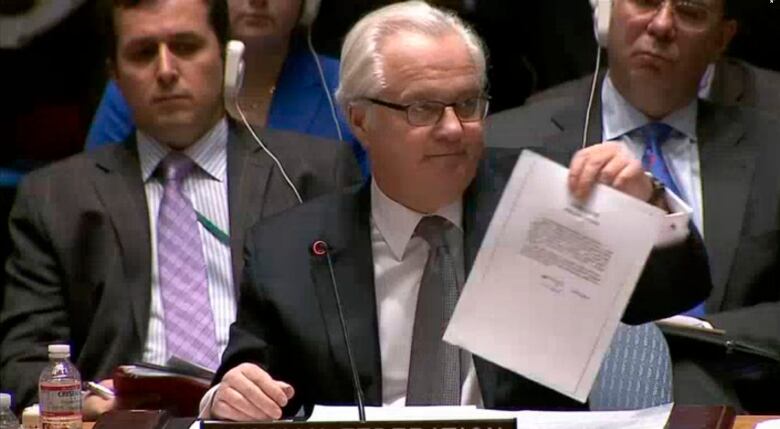

On Monday at an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council, Russian and Ukrainian officials argued over just how many Russian troops are allowed to be deployed in Crimea under existing treaties governing Russia's use of the Sevastopol naval base. Russia said 25,000 while Ukraine insisted on 11,000.

3. How will the West react?

"There's very little the West can do," says Way of any possibility of Western intervention in Crimea. "Russia is a big country, it has big army, it has nuclear weapons, it provides a good chunk of the energy for Europe. You really cannot tell Putin what to do."

The leaders of the U.S., Canada and European countries have signalled that they may pull out of the June summit of G8 counties in Sochi in protest over Russia's actions in Crimea, and several countries have threatened to impose economic sanctions on Russia. On Monday, the United Nations held its third emergency meeting of the Security Council on to discuss the Russian incursion, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe has said it will send monitors to Crimea.

But the three experts we talked to all agreed that such actions are unlikely to have much effect on Russia itself.

"This is obviously going to isolate him and undermine the Russian economy, but clearly, he's already taken that into account."

NATO's hands, too, are tied, says Jeff Sahadeo, director of the Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies at Carleton University. It learned its lesson in 2008 in the Georgian-Russian war over South Ossetia when it sent ships to Georgian ports on the Black Sea and Georgia took that as sign that it would back its incursion into the autonomous region on the Russian border.

"If they make even pro-Ukraine statements or move warships or scramble forces, that might [inspire] some of the more radical forces in Ukraine to think they're going to get support from the West and try and trigger some kind of provocation, which is what happened in the Georgian case," Sahadeo said.

4. Will Crimea play out like South Ossetia?

Many have compared the current situation in Crimea to Russia's intervention in the autonomous region of South Ossetia in Georgia in 2008, but analysts say there are key differences. Russia's entry into South Ossetia was not a simple case of military aggression, says Way, but was provoked largely by Georgia's attempt to assert control over the region by launching a military assault.

"Here, there is absolutely zero provocation by the Ukrainian authorities," said Way. "They're [Russia] talking about defending themselves, but against whom? It's totally unclear. This [threat] is completely manufactured."

While Russia exploited the discontent in South Ossetia in order to de facto remove the autonomous region from Georgian state control, the stakes this time are much higher, said Martin.

"The symbolic and geopolitical importance of Crimea dwarfs South Ossetia," he said.

Today, Russia considers South Ossetia — and another breakaway Georgian territory, Abkhazia — to be independent, but most of the rest of the world does not recognize these territories as sovereign states. It remains to be seen whether the Crimean conflict will result in a similar outcome.

5. What do the pro-Russia Ukrainians want to happen?

Although Crimea and eastern Ukraine have large Russian populations and pro-Russian actors likely helped Russia execute its incursion into Crimea, that does not necessarily mean these regions want to split from Ukraine and join Russia.

The elites in eastern Ukraine do not want to become provinces of Russia.—Terry Martin, historian, Harvard University

Pro-Russia sentiment in the east and south has been stoked in the aftermath of the violent protests in Kyiv by activists who took their cues from their counterparts in western Ukraine, who organized large rallies and took over regional governments, says Way. This, he and Martin say, has perhaps created an inflated impression of pro-Russia support.

"Even in Crimea, would there be major support for separation from Ukraine? Probably not at a calm time," says Martin. "Would there be anywhere else in Ukraine? It does not seem so, and, moreover, the elites in eastern Ukraine do not want to become provinces of Russia....

"These elites have a good situation in Ukraine. In Russia, they'll just be some third-rate, fourth-rate, fifth-rate oligarchs, and they'll be under somebody that has shown he can deal with oligarchs."

Ukraine's eastern elites will be perfectly happy if Russia's recent intimidation tactics lead to a better deal for them within Ukraine, and they are already being courted by the new interim government, which has begun appointing the east's most powerful oligarchs to governorships in eastern Ukraine.

"It's a smart move," says Martin. "These are the people who can create trouble."

The other population to keep in mind are the Tatars, who make up about 12 to 15 per cent of the population in Crimea (to Russians' 60 per cent) and consider themselves the people most indigenous to the region. They have a fraught history with Russia and have generally allied themselves with the Ukrainian part of the population. Although their ultimate hope would be to have their own autonomous Tatar republic, "they're realists," says Martin, and are likely to favour remaining part of Ukraine over Russian annexation or Crimean independence.

6. Who will fund a bankrupt Ukraine?

Ukraine is on the brink of defaulting on its debt and needs about $35 billion US over the next two years to stay solvent, according to its interim finance minister. With the $15 billion Russia promised the country under Yanukovych's regime now off the table, Ukraine needs a new benefactor — and fast.

The International Monetary Fund has pledged its support and will likely provide short-term financial aid to shore up the country's currency and ensure that basic payments such as pensions and government salaries are made, but ensuring that whoever comes to power in the elections planned for May puts future bailout funds to good use is the greater challenge, says Sahadeo.

When you have a lot of guns and a lot of young conscript soldiers who have been pumped full of nationalist rhetoric and are nervous, that's the real danger.—Jeff Sahadeo, political scientist, Carleton University

"I think there are a lot of questions that the U.S. and Europe have to ask themselves about whom do they tie their fortunes to," he said.

"The U.S. and the EU are just kind of avoiding the question right now. In a way, the focus on Russia makes it a little bit easier for them to not talk about it."

The smart move for Putin would be to de-escalate the current situation and sit back and watch the West try to deal with the mess that is the current state of Ukraine's economy, Sahadeo said.

"Putin could probably look good just by sort of swooping in a year from now and saying, 'OK, the West has failed you. I'm here now … I have your interests at heart,'" he said.

7. What is the biggest future threat?

"The one thing I worry about is the unpredictability," says Sahadeo. "When you have a lot of guns and a lot of young conscript soldiers who have been pumped full of nationalist rhetoric and are nervous, that's the real danger — that there'll be some kind of unscripted confrontation that will lead to one person firing a weapon and a few more people firing a weapon and the civilian population getting involved. That's something that really makes me nervous much more than something happening at the international level."

Another real threat, says Sahadeo, is that the well-armed nationalist groups who succeeded in ousting Yanukovych will carry out some kind of guerrilla actions against pro-Russian forces within Crimea or in the eastern regions.

"Let's say a conflict in Donetsk broke out and the pro-Russia leadership in Donetsk appealed to Putin for intervention, then what then? That's where it gets really scary."