How teleprompters and canned campaign speeches may be hurting our democratic system

'I think it's really pushing people away from politics,' says activist and author Dave Meslin

Originally published on Sept. 14, 2019.

This story is part of Day 6's Democracy Divided series. Each instalment takes a close look at the health of the democratic system in Canada leading up to the Oct. 21 federal election.

A five-week long federal election campaign will offer plenty of chances for Canadians to engage in the democratic process, but political activist Dave Meslin, who swore off party politics after becoming disillusioned as a campaign volunteer, believes modern campaigns are actually part of the problem.

"There's lots of reasons why people are tuning out, and one of the biggest problems is the way that political parties campaign, the way they speak to us, and the way they engage their volunteers," Meslin, the author of Teardown: Rebuilding Democracy from the Ground Up, told Day 6 host Brent Bambury.

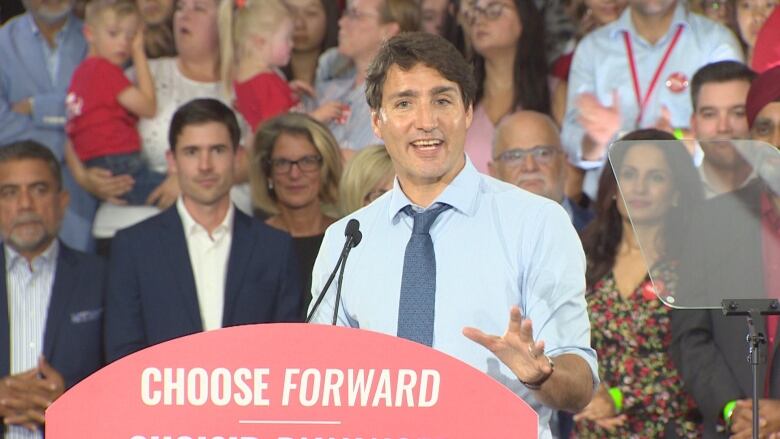

Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau triggered the campaign on Wednesday and the Oct. 21 election will offer Canadians a chance to weigh in on the issues that matter most to them.

But according to a recent CBC News poll, nearly 50 per cent of Canadians feel that none of the parties on offer accurately represents what they care about most.

More than a third of Canadians don't think their vote will make a difference.

Meslin told Day 6 host Brent Bambury why he believes modern political campaigns are hurting Canadian democracy.

Here's part of that conversation:

You've been immersed in Canada's political landscape for decades. How broken is the modern political campaign?

I think it's a mockery of what it could be. And I think we've reached a point where we probably even have trouble imagining what an exciting and inspiring election would even look like.

But I'm encouraging you and your listeners to try and do that. Imagine knowing an election is coming up and you feel motivated about that because it's an opportunity to discuss ideas, to shift leadership, to see new, bold ideas implemented, and you're like, 'Oh cool! Election!'

I don't think many people are feeling that way right now.

Twenty years ago, you actually were a campaign volunteer for the NDP and you hated that experience so much that you swore off party politics forever. What made it so disillusioning for you?

I really wanted to get involved and I ended up in a campaign office during an election, and I kind of imagined that the volunteers would be trained on the issues, on the platform, and that we would go out as messengers and try and persuade voters.

In the end, I learned that all these partisan campaigns really just use their volunteers as data collection assistants. And they're collecting data on how every person in each house is planning on voting for the sole purpose of harassing them on election day to remind them to vote.

There's very little data to show that it makes a difference.

And what was the opportunity that you thought was being lost?

I think the opportunity being lost was hundreds or thousands of discussions at the door between neighbours. It's the one time of the year when people actually have questions and want to hear what the platforms are, especially from a neighbour.

We spoke to Linda Duncan who's an outgoing NDP MP from Edmonton and she says that volunteers are discouraged from talking to voters for a reason. Here's Linda:

LINDA DUNCAN: Frankly, the last thing that you would want is one of your campaigners to get into an intense dialogue on a policy matter because that's the role of the elected official, or the person who's running. That's not where the debate should occur.

Dave, does Linda have a point there? Is it impractical to expect that much from canvassers.

No, I think it's really condescending.

I think it would take some training but I think of other groups who depend on canvassers ... and they all come trained with the message.

There's lots of models out there of how you can train an army of volunteers and it absolutely can be done. And I think it's really telling what she said because I think parties don't trust their volunteers. I think parties don't trust their membership. I think these days parties don't trust their caucus.

We know how centralized power has become within each party. MPs are telling groups like Samara they don't feel that they have a voice in parliament because the parties don't trust them to speak.

So what we have is these big, institutionalized bureaucratic parties that don't trust anyone to open their mouth except for the leader. And then the leader is very scripted and they read off teleprompters and the whole thing becomes so boring and not authentic.

And not focused towards the voter. In a recent CBC News poll, a quarter of Canadians said that they didn't have enough information to cast an informed vote. They're not getting it from anybody.

Where would they get it from? And here's the punchline: during this time when political strategists have allegedly mastered the art of identifying votes and getting out the votes, voter turnout has gone down.

And also there's something very cynical about identifying the vote which is that it would actually take less time and effort to simply remind everyone to vote on election day.

If you think about that, the political parties don't make a list of their supporters to remind them on election day. They make a list of supporters to make sure that they don't remind the wrong people on election day.

In that sense, it's the largest attempt at vote suppression we've ever seen.

That's the internal side of a campaign, but let's talk about the public facing side of the campaigns. You've pointed to campaign signs — the physical signs — as another symbol of the brokenness of our election cycle. What's wrong with the signage?

All the campaign events are so heavily choreographed. So the two things that really bothered me — because I was able to see how these things were planned and on the inside by being involved with these campaigns — one was the teleprompters not letting very eloquent leaders actually speak.

We don't see a lot of authenticity and what that does is it opens up the field for vacuous, angry and often racist and misogynist leaders to go off-script and suddenly seem like they're the only ones who are actually speaking from the heart.

But the other thing was the signs. So the most exciting types of signs we see at rallies are ones that are handwritten. And we saw that with the Occupy movement, Women's March and Tea Party, so on the right and the left.

Part of me is tuning it [the campaign] out. I've become so disappointed with everything about our political culture because we're not being offered real choice.- Dave Meslin

What I saw happen is about 20, 25 years ago, is slowly parties really pushed away from that. And then it got really weird. They started doing these 11" by 17" placards, one colour, and they would always have the most hollow, condescending message that says nothing.

I'll just give you a few examples: "Strong leader, real plan," and "New mayor, better city." And what I do in the book is I point out how ridiculous it would look in any other context.

If a rock band was playing a show and they had 30 people holding up signs saying, "great song" or "amazing concert," there's something childish about it.

Since the announcement came on Wednesday, you're another Canadian citizen receiving this barrage of messages from leaders and candidates. How do you feel about what you're hearing?

To be honest, part of me is tuning it out. I've become so disappointed with everything about our political culture because we're not being offered real choice.

I mean, let's be honest, in this election one of two parties are going to win: the red or the blue. And it's the same two parties who've been changing power back and forth for 150 years.

Imagine Netflix having only two movies and it's the same movies your grandparents watched. I mean no one would subscribe to that and that's what we're being offered.

So I'm not really tuned into what Scheer and Trudeau are selling this week because I don't think this election can possibly live up to what my imagination offers for what an election could be in Canada.

Is there a chance that this whole thing is just a bitter pill that we have to swallow in order to see a credible candidate get elected?

Perhaps. Under first past the post, there's certain techniques that work very well, so I feel really bad for the Green Party. I think it's really hard to run a campaign in almost any riding in Canada because the truth is a lot of those votes don't count.

I think we won't hear a lot about policy; we'll hear a lot about strategic voting. A lot about why you should be scared of the other parties and then why we're the only party who can stop that.

Obviously you think that our election campaigns are not evidence of a healthy democracy and yet here you are, you're still engaged politically in many, many ways. What is your message to Canadians ... who are so frustrated that they're considering walking away from the whole thing?

I see so much evidence on the ground that people care. The fact that even though our elections are so stale and boring, two-thirds still show up to vote.

But more importantly, all the kids who are walking out of school to protest against climate change or class cuts, we constantly see reminders in the news that people care about issues and are willing to invest time and energy when they feel that that investment will make a difference.

So what I'm really focused on is proposing and fighting for real concrete changes that could completely transform our political culture into something that we all enjoy and benefit from.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity. To hear the full interview, download our podcast or click Listen above.