Machine consciousness is 'hugely problematic,' says Ian McEwan

Author of Machines Like Me discusses the messiness of human morality and our future with AI

This story was originally published on May 17, 2019.

We've all been there.

You're frantically trying to remember the name of an actor from the show Cheers but your Alexa smart speaker thinks you're asking where to buy beer.

Now you're shouting at an inanimate object, calling it names. But this machine you bought can't even register your human emotion of frustration, because it's not sentient.

But what if it was?

Can we own a consciousness? Is it possible to purchase and operate someone else's subjective experiences? These are the deep and uniquely human questions at the root of Ian McEwan's novel Machines Like Me.

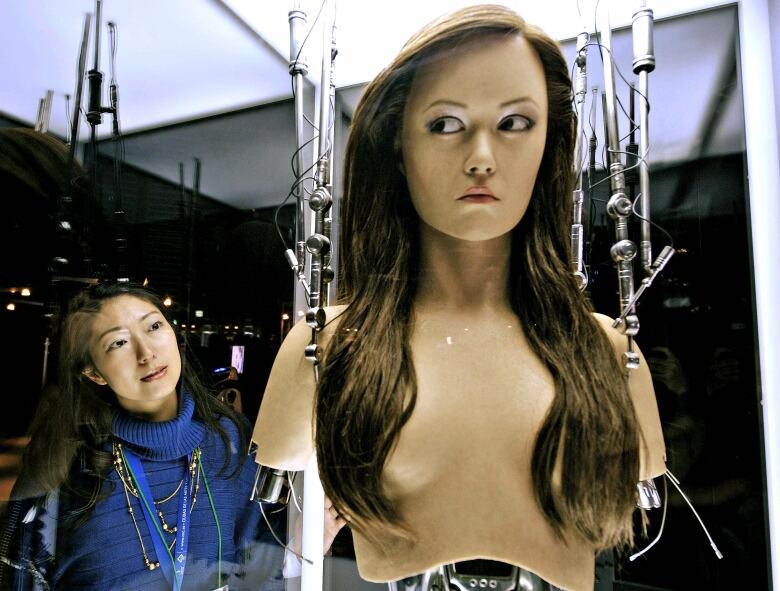

In an alternative 1980s U.K., a couple named Charlie and Miranda purchase Adam, a highly realistic humanoid robot who comes to live with them. The resulting tale includes a love triangle, questions of machine sentience, and whether our human morality extends to AI beings.

"'Can we own consciousness?' is at the heart of that, and the narrator havers [babbles] between thinking that the Adam he buys is actually just a very complicated sophisticated computer game or a consciousness as real as his own," explains Ian McEwan.

The author spoke to Spark host Nora Young about the themes of the novel and what it really means to be human. Here is part of their conversation.

Could you ever have an artificial consciousness that could understand this messy way we live?

Well, my hope is that it will help us. Many people have pointed out that creating some imitation of ourselves will, in part, entail understanding what we ourselves are. My optimistic hope is that creatures like Adam will come among us and give us a clearer understanding of what and who we are.

We don't even really know what human consciousness actually is. Do you think we'll be able to replicate it?

I think it's a very long way off.

You're looking at 100 billion neurons with 7,000 axons, on average, connecting with each neuron. The whole thing liquid-cooled and running on 25 watts – the power of a dim light bulb. We are nowhere near anything like that, especially without overheating. We don't even have a battery!

But even though we recognise that a machine could think many times faster than us in half a second and make some good choices, I think [this] should make us very uneasy about this transfer of authority.

Anyone whose car has broken down and has given it a good kick is already in an emotional relationship with a machine.- Ian McEwan, author

Given our tendency to anthropomorphize the technologies in our lives, I wonder if we are creating moral dilemmas for ourselves regardless of whether they have consciousness. I mean, we have conversations already about, "Is it okay to bark out orders to Siri or Amazon Alexa?" or, "Should you say please?"

Anyone whose car has broken down and has given it a good kick is already in an emotional relationship with a machine.

So I think once we get something extremely clever like Adam, we're going to fall into this trap of ambivalence. We all want to give it consciousness and yet, at the same time, we'll be thinking it's only wires.

If you could imitate or even just regard in a kind of "black box" way, the human brain, if you could replicate it, then you would have all the necessary conditions for a consciousness.

But we all have to accept we're all stardust. We have to regard them as our cousins from the future.

What about in your own life. Do you use Siri on your phone or have an Amazon Alexa in your home?

Yeah, I speak to Siri. I don't say thank you or please. We have an Alexa-type machine. I think actually, following the latest revelations, I am going to unplug her.

It's pretty useful for looking up some pop song that everyone's forgotten but apart from that, I haven't really found much use for it.

One of the points that you make about our relationship to technology in the book is how quickly we become bored of our shiny new objects. Do you think this is a new phenomenon?

I think we're the first to live through such velocity of technological change. It's as if we were children on Christmas Day ripping open one present and instantly ripping open the next.

Think of an airplane trip, hunched up in economy on some domestic flight. You could have Charles Dickens next to you taking the window seat and let him remind you what a marvel it is to be 1,000 metres up above the clouds.

He would be struck with wonder while we just think of it as a nuisance we've got to get through to be elsewhere.