Coronavirus is airborne so stop disinfecting everything: expert

UBC professor says improving ventilation should be a focus of COVID-19 prevention

Stop cleaning and start ventilating — that's the message from Michael Brauer, a professor in the School of Population and Public Health at UBC.

Given the scientific consensus that the coronavirus is airborne, Brauer is calling for a shift in COVID prevention strategies.

"We are at a point now where I think we really have quite convincing evidence that airborne transmission is the primary route of transmission. And we need to emphasize the things that we know work for that … and deemphasize the things that we know really aren't that effective … like the cleaning of surfaces," Brauer told Dr. Brian Goldman, host of The Dose and White Coat, Black Art.

Last week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated their website to acknowledge that the coronavirus is airborne. The World Health Organization did the same in April. The Public Health Agency of Canada updated its COVID-19 guidelines to include the risk of airborne spread in November.

A Lancet report published last month from epidemiologists and experts in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K. found overwhelming evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is spread through aerosols — tiny airborne particles that come when an infected person exhales, speaks, shouts, sings, sneezes, or coughs, and can linger in the air for hours.

Focus on these prevention measures

Brauer said embracing the science of airborne transmission means we should shift our focus to prevention strategies that work to reduce the spread of aerosols:

-

Ventilation: Improved ventilation indoors needs to be a key focus, said Brauer. That can mean opening windows, upgrading mechanical ventilation systems, and using filters to reduce particles in the air. "We should be trying to make the indoors like the outdoors, meaning trying to get as much fresh air into that indoor space as possible." He'd rather see businesses and schools spend money on better ventilation than on things like plexiglass dividers that aerosols can rise above.

-

Distancing: Keeping a distance of more than two meters from others is important because, the further you are from someone else, particularly indoors, there's more ability for the air around you to dilute those small aerosolized particles.

-

Go outdoors: Take your activities, wherever possible, outside. Aerosols get diluted quickly in the fresh air.

-

Masking: Mask-wearing is an effective COVID prevention strategy. Brauer said a regular non-medical mask is fine in most circumstances, but if you have a higher potential for being exposed to the virus, a mask like an N95 respirator is a better choice.

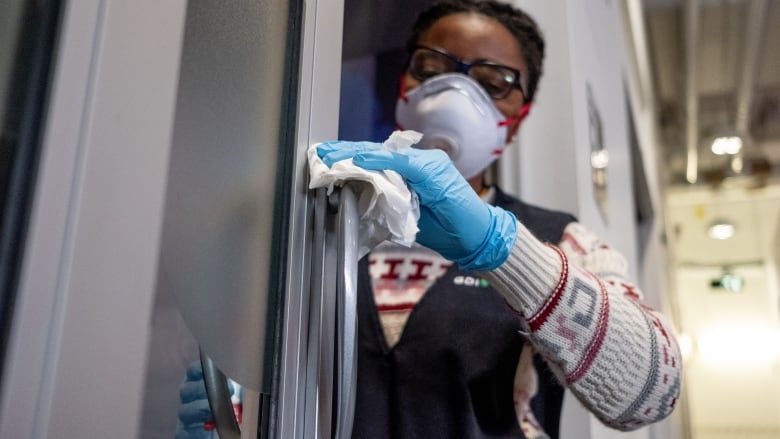

Stop disinfecting

While handwashing is still recommended, Brauer and other experts say it's extremely rare for the virus to spread through surface contact; constantly disinfecting surfaces could actually be damaging to our health.

Tara Kahan is an associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, and Canada Research Chair in Analytical Environmental Chemistry. She studies the use of cleaning products and their potential harms.

"I find [the COVID disinfecting] horrifying because in our efforts to protect ourselves from COVID we're doing something that isn't useful generally but it actually can cause real harm."

There is considerable evidence in numerous studies, said Kahan, that common household cleaning products can negatively impact health, and can cause or worsen conditions like asthma and respiratory issues. They're even associated with some cancers.

"Almost any of these products that are billed as disinfectants or for sanitizing can emit a lot of things into the air," she said, and they have the potential to cause harm.

Kahan offered a quick science lesson: Many cleaning products release something called volatile organic compounds, which like to rise into the air from the surface they're applied to. In the air, they can react with all sorts of things in the environment, like skin oils and sunlight. This reaction can turn them into aerosols, which can cause irritation or damage if breathed into your respiratory tract and lungs.

Don't mix cleaning products

"One of the most dangerous things is that people are sometimes combining cleaners. Since the pandemic hit, poison control calls have increased dramatically because of people accidentally or purposely mixing different cleaning agents," said Kahan.

Combining cleaning products can create potentially harmful gases. In the worst-case scenario, mixing can even be fatal. At an outlet of the restaurant chain Buffalo Wild Wings in Massachusetts in 2019, an employee died from the toxic fumes generated when two cleaners — acid and bleach — were accidentally mixed.

WATCH | What makes a cleaning mix toxic:

Decoding labels

Kahan said it's difficult for people to make good choices about cleaners because ingredient lists can be confusing and hard to understand.

"I don't expect people to read through a list of ingredients and say 'is tetrasodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate bad?'"

Instead, her advice is to follow these practical tips for cleaning safely:

-

Soap and water is usually all you need.

-

If you want to use something more, hydrogen peroxide diluted in water works well.

-

Disinfecting is usually not necessary, but if you feel the need, make sure you read the instructions and don't combine products.

-

Try to use something that is not scented. Added scents can release those potentially dangerous aerosols.

-

Ventilate by opening the window, if possible.

-

Clean quickly and leave the room right after you're finished.

"I don't want to freak everybody out," said Kahan, noting that if you follow these guidelines, you can minimize the risk. But she said she worries most about people cleaning frequently and in places with low ventilation.

"The best way of protecting ourselves from COVID is also the best way to make our homes and buildings healthier in general [through good ventilation]."

Written and produced by Willow Smith.